Hi, everyone! Welcome to Prog Progress, a blog series in which I journey through the history of progressive rock by reviewing one album from every year of the genre's existence. You can read more about the project here. You can learn about what I think are some of the roots of progressive rock here. You can see links for the whole series here.

Throughout this project, I've selected albums that I thought were significant to prog's development, but that's also happily coincided with albums that, for the most part, I enjoy (and often even love). But now we've arrived at 1978, which is, uh, putting it lightly, not a good year for progressive rock. Yes put out Tormato, an album whose cover alone is so bad that members of the band itself apparently threw tomatoes at it; Genesis, absent now Peter Gabriel and guitarist Steve Hackett, left prog behind entirely as Phil Collins took the reigns in ...And Then There Were Three..., and the same went for Gentle Giant (whom I didn't ever get a chance to cover in this project, but whose records in the early-to-mid '70s stand toe-to-toe with a lot of what I have covered), whose album Giant for a Day! turned the band's music sharply toward limp pop-rock and whose cover turned their already kind of hokey Giant mascot into what looks like one of those painted plywood standees at an amusement park telling kids how tall they must be to ride the roller coaster. I mean, outside of Rush's pretty good Hemispheres (whose cover you may remember for its bold juxtaposition of brain tissue with tightly clenched buttocks[1]) and Camel's very good Breathless (as well as Popol Vuh's soundtrack for Werner Herzog's Nosferatu remake, if we're counting that as prog), it's basically all bottom-tier stuff like that. I did consider covering Breathless for this year's entry, since it anticipates a lot of where prog would go in the '80s and is, you know, fun to listen to. But ultimately, I decided that would be disingenuous and unrepresentative of the trash fire that is Progressive Rock, 1978. So I reluctantly arrive at Emerson, Lake & Palmer's 1978 release, Love Beach. Ah, Love Beach—much more representative.

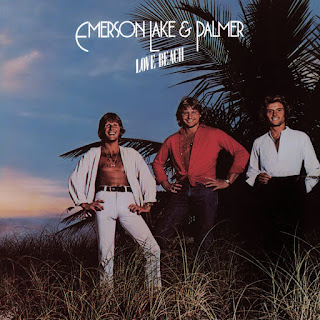

Love Beach is terrible, y'all. There's no other way to slice it. The songs are bad; the lyrics are bad; the instrumentation is bad. Heck, you don't even need to get that far—just look at the album cover[2]! Those plunging necklines! That necklace! That chest hair! Those tans! Is this a Jimmy Buffett album? A photo from a vacation taken by the cast of Saturday Night Fever? I wish, because either of those options would have been preferable to what it really is: the nadir of '70s progressive rock and by a considerable margin the worst CD in my home collection (the things I do for this project...).

It wasn't always this way. It didn't have to be this way. When Emerson, Lake & Palmer formed in 1970, their future was so promising. Keyboardist Keith Emerson was fresh off of a successful run as a full-time member of The Nice (who were sort of a Moody Blues-ish group with an affinity for making rock arrangements of classical music); singer and multi-instrumentalist Greg Lake was a founding member of King Crimson and had played a central role in the recording of that group's first two albums; drummer Carl Palmer had spent time in both the Crazy World of Arthur Brown and Atomic Rooster. If not prog's absolute best and brightest (I mean, if only Lake could have dragged over Robert Fripp...), the trio were certainly not without impressive CVs and, requisite of prog's ambitions, all instrumental virtuosos. It all paid off handsomely on their self-titled debut in 1970, a commercial smash, a front-to-back excellent piece of early prog, and whose song "Lucky Man" was a staple of rock (and later classic rock) radio for years. This album established all the major ELP calling cards: virtuosic instrumentation that jumped from jazz to folk to hard rock to classical on a whim, extended solos that highlighted the strengths of the individual band members, lots of Moog synthesizer, and an affinity for doing straight-up re-arrangements of classical pieces (a proclivity likely imported from Emerson's time with The Nice)—this time, it was Bartók's "The Barbarian," which opens the album.

On an artistic level, the band never topped their debut, and as the years passed, they became something of a critical punching bag, even as their commercial success remained steady—to this day, albums like Tarkus (their sophomore effort, featuring a 20-minute sci-fi suite about a gigantic mechanized armadillo or something, which the album proudly emblazoned on its album sleeve) and Brain Salad Surgery (their fourth LP, whose climactic, 30-minute composition "Karn Evil 9" provides the immortal line of unintentional prog self-critique: "Welcome back, my friends, to the show that never ends") are held up as examples of the bloated excesses and grandiose pretensions of progressive rock. However, while some of this stuff is undeniably silly (and every album after their debut has at least one shockingly bad song [ex: Brain Salad Surgery's "Benny the Bouncer"]), I think there is also quite a bit of good material in those first half dozen ELP records alongside some of the kind of dumb stuff. Golly, I'll even stick up for parts of "Karn Evil 9" and a good chunk of "Tarkus," and oftentimes, even the silly stuff is sort of endearingly goofy rather than gratingly zany—like, an armadillo tank? Come on, that's kind of amazing. Aside from the band name's flagrant disregard for the Oxford Comma, I have no real beef against Emerson, Lake & Palmer.

Until you get to Love Beach. Friggin' Love Beach.

Honestly, a huge part of the problem is precisely the lack of the silly stuff. There are no armored armadillo tanks or 30-minute suites built around a lame Carnival / Karn Evil pun; there's barely even a classical arrangement—"Canario," a four-minute instrumental rendition of the fourth movement of Joaquín Rodrigo's Fantasía para un gentilhombre, feels like a tossed-off afterthought of fill-in-the-blank ELP instrumentation. What we get instead are lyrics about [*shudders*] love. Not sweet love either; no, this is the '70s rock star version of love. A real lyric: "Help yourself to a taste of my love / Call up room service / Order peaches and cream / I like my dessert first / If you know what I mean." The song goes on to say, profoundly, "Yeah, taste it, taste it, taste it / Around the maze of pleasure," later beckoning the song's subject to "get on my stallion / and we'll ride." If I had more confidence in Greg Lake's wit, I would call this a parody of rock lechery; as it stands, though, I think it's sincere, and alongside gems like the title track's couplet, "I'll keep you satisfied / My love won't hide" (or, let's not forget: "I'm gonna make love to ya on Love Beach"), it sounds like the band was just making bad love songs. We've traded wizards and circuses and mech battles and whatever other fun, uncool stuff ELP was singing about in their previous albums for the stalest and grossest of rock clichés, and it's boring and terrible and makes me so very sad and tired. Even the obligatory side-long suite, "Memoirs of an Officer and a Gentleman" is dull; not a hint of science fiction or metaphysics or anything here; just a really impassively told romance between a WWI officer and the woman he pines for from the front ("Girls, oh there were girls," the speaker sings at one point, just so we haven't forgotten how bad ELP is at writing lust). It's a tired trope to evoke Spinal Tap when classic rock bands fall on creatively bankrupt ideas, but... I mean, this is exactly the sort of stuff Spinal Tap writes. Only ELP is serious.

Look, I don't mind love songs. But these love songs are just so embarrassing; it's like they were written by people who have never felt a sexual or romantic thought in their lives but who, having studied the canon of Led Zeppelin and Aerosmith and the Scorpions, taking copious notes and creating diagrams of the lyrical patterns and emotional cues, produced this uncanny simulacra of human sexuality that's somehow both naive and uncomfortably well-informed. I just want to reach back into 1978 and pat these dudes on the back and say, "It's okay, guys; thanks for trying, but you don't have to write about sex." Neither the critical nor the commercial rock canon leaves much room for asexuality, and while I kind of doubt that any of the members of Emerson, Lake & Palmer identity as asexual ("brain salad surgery" is apparently slang for fellatio, so...), that's definitely where their artistic comfort zone lies. People like to focus on the long compositions and fantasy lyrics when they talk about the hallmarks of prog, but I don't think it can be discounted as part of the genre's appeal just how little progressive rock cares about sex; it really is one of the few arenas of rock and roll where masculine virility isn't a key part of the ethos, and as such, it's something of a haven for people who find that kind of posturing oppressive or silly or just simply don't have an interest in the relentless service of the libido. The rare occasions where prog does acknowledge sex (like this album, or this Gentle Giant cover) are, in addition to being juvenile and off-putting, jarring intrusions into a largely asexual world.

This is a huge part of what's so dispiriting about the fall of progressive rock at the end of the 1970s. I dismissively alluded to Gentle Giant and Genesis creating "pop-rock" music early in this post, and I just want to make it clear: what's depressing about that isn't that there's something inherently bad about pop-rock; it's that it's a violation of an ethos, a rejection of those who might have found a niche within the singular world that progressive rock created in favor of an opportunistic spirit of mainstream embrace. And that's compounded by the simple fact that most prog bands simply weren't that good at the whole pop-rock thing. I'm wearing some pretty heavily rose-colored glasses, I know; the progressive rock scene was full of the same kind of toxicity that any commercially lucrative music attracts. But in the same way that a lot of people look at glam rock not for its realities (e.g. statutory rape, drugs, whatever) but for its ideals (gender-bending, queer inclusivity, emotional sincerity), I think there's a similar argument to be made for progressive rock's bookish, outsider ethos as a place for those looking for a respite from the normalized culture of rock's canonical mainstream, even if the specific musicians don't measure up to that ethos. Admittedly, genres evolve and close fandoms can be as toxic as the "normie" culture they reject. But in the case of prog rock, the push toward the mainstream feels, in most cases, so craven and barren of ideas that my sympathies definitely lie with the fans left behind on this one.

This is certainly the case with Love Beach, which, behind the scenes, was absolutely a grab for money by chasing the trends of a changing rock landscape. In the liner notes for the 2017 reissue of the album (which I own, because I'm committed to my research, dammit!), Greg Lake remembers the album's inception; what he says is revealing: "We went to Ahmet Ertegun, the president of Atlantic Records, and explained to him that we didn't really want to make another ELP album. He was very concerned. He said 'You owe us another record. If you don't do it, we won't support your solo stuff'.'" More revealing still is Keith Emerson's memory of the album's production: "Much to my reluctance, a commercial album was suggested, meaning we would have to compress all the simpler ideas and make them into neat little singles." It's not as if Love Beach is some passion project; it's pure music industry cynicism. "We didn't really have much belief in the project," Lake goes on to say. Atlantic flew the band out to the Caribbean to record, hoping to ease some of the musicians' weariness, but that apparently made things worse. Lake again: "We spent more time in the studio than on the beach. Every day we'd go in there at 11 am just as the beautiful sunshine was coming out, and we had to go in this darkened room and come up with music. When we came out it was dark already. We felt we had just missed another lovely day."

I'm not here to tell you that Emerson, Lake & Palmer are some tragic music-industry sacrifice à la Syd Barrett in Wish You Were Here; they went to a resort to record an album, for goodness sake. Nor am I here to paint them as misunderstood geniuses [3], because they are clearly not. They are simply progressive rock's consistent middlebrow. And just as you can also take the temperature of a society's health by looking at its middle class, I think the same can be done of a genre and its middlebrow—and boy howdy, when the industry is forcing the kind of work out of a genre's middlebrow as Atlantic did of ELP on Love Beach, you know you're on a sinking ship. As Greg Lake muses, "In retrospect, I should have stopped for a while and regained my equilibrium."

So say we all, Greg.

Until 1979...

1] If there's one thing worse than prog's 1978 music, it's prog's 1978 album covers. Woof.

2] 1978 strikes again!

3] Unlike the reissue liner notes, in which this is a real sentence that exists: "ELP were no longer fashionable, and 'prog rock groups' were deemed extinct dinosaurs, when actually they were sleeping tigers still ready to do battle, with their claws drawn."

No comments:

Post a Comment