Hello all! I'm working my way through AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies

list, giving thoughts, analyses, and generally scattered musings on each

one. For more details on the project, you can read the introductory

post here.

Three very different movies in this post. And... that's all I have to say about that.

76. Forrest Gump (1994, Robert Zemeckis)

Look, everyone, unlike a lot of contemporary critics, I don't hate Forrest Gump (in fact, I even like it), and that whole "Forrest Gump vs. Pulp Fiction at the Oscars" is pretty dumb because, come on, I think we all know that the right position in that debate is actually The Shawshank Redemption. But I've never understood the huge, huge cultural cachet the film has with contemporary audiences. I mean, it's a pleasant movie that, somewhat amusingly, plays lip service to Baby Boomer culture while also positing that said culture is basically the accidental offspring of a mentally challenged man from Georgia. There are some truly groundbreaking effects used throughout, too, and consequently, the film has a winsomely, even at times anarchically, playful streak with history (e.g. Forrest mooning LBJ), which makes the whole affair a little less self-aggrandizing and more punk than the movie's detractors give it credit for. Oh, and the acting is uniformly excellent, too. So no, I'm not immune to the movie's charms. But a generation-defining movie? A great movie? One of the greatest movies movies of all time? I don't see it. Of course, people are allowed to have their own opinions, and I wouldn't dream of telling people they're wrong (or dumb or evil or whatever) to love this movie. But to those who do love Forrest Gump, I have a few questions I sincerely want answers to: 1) What exactly is profound about having Forrest experience or orchestrate so many of the late 20th century's cultural touchstones? It's funny, but what does it mean? 2) How is Forrest anything other than a blank slate of a character, and how does this make him a compelling protagonist? 3) What is the film doing with Jenny other than creating a love interest for Forrest? What's the point in transforming her from a character with personal tragedies (abusive father, etc.) into one who shoulders Society's tragedies (post-hippie fallout, etc.)? It seems like the movie really, really wants her to represent something about the Boomer generation, but what? 4) Why is "Run, Forrest, run!" one of this movie's go-to quotes? It's not funny, deep, clever, poignant, or anything. I mean, Forrest has to run away from kids pelting him with rocks (and pretty big rocks, too!); that's a dark context for a quote shouted willy-nilly at runners everywhere, isn't it?

77. *All the President's Men (1976, Alan J. Pakula)

You'll have to forgive me if I'm a bit over-the-moon about this one. See, when it's done well, the based-on-a-true-story thriller (e.g. Zero Dark Thirty), particularly in its more political shades (Charlie Wilson's War, Lincoln), is one of my favorite movie genres ever, and it's an even greater favorite when that genre mixes in a healthy excitement for journalistic rigor (Zodiac). Ladies and gentlemen of the blogosphere, All the President's Men is just such a thriller, and a masterpiece of one, too. It's definitely one of the best movies I've watched for the first time for this 100 Years...100 Movies project, and by golly, there's a really good chance that it will go on to become a new favorite of all time for me. It's funny, tense, insightful, and genuinely exciting, impressive characteristics in their own right made all the more impressive by the fact that this film achieves them almost entirely through dialogue. I mean, think about this: All the President's Men is a movie with no chase scenes and no killings (and that alone says volumes about what a cinematic feat this thriller is), a movie whose biggest setpiece is the buzzing office of the Washington Post newspaper, a movie with few (if any) dynamic characters, a movie in which the solution to its major mystery is one of the most well-known events in American history. This is not the typical blueprint for an "exciting" movie, and yet All the President's Men is unquestionably one (to me at least). I'm tempted to attribute that excitement to Dustin Hoffman's glorious, glorious hair (just look at those flowing locks!), but honestly, it's the partnership between the dialogue and the wholly unpretentious cinematography. Every line moves the film forward, and every shot frames that line's delivery in the most informative way possible. The film takes to heart the journalistic ideals of clarity and efficiency, which is only fitting for a movie whose centerpiece is a crackerjack bit of journalism. To that effect, All the President's Men is one of the great successes in translating journalism to film and a fantastic bit of proof for the theory that when you've got a good story, the best way to tell it is often to step back and let it tell itself.

78. Modern Times (1936, Charlie Chaplin)

Of all the Chaplin movies I've seen, Modern Times is by far the most caustic, preachy, and socially conscious (though, to be honest, I haven't seen any of his later films, such as The Great Dictator, that have a reputation for actually being preachy, etc.). This is a movie all about the oppression of the working poor by the machinations of management and, of course, the System as a whole, and while these themes are present in plenty of Chaplin's work, Chaplin really goes whole hog into them in Modern Times. This is definitely a Populist work (like, in the political sense), so if you have an aversion to that, I might suggest steering clear. Only... no, I'm not going to suggest that, because Modern Times is an awesome movie, regardless of its (or our) politics. In another movie, all that preachiness might have made the whole enterprise a leaden bore, but the good news about Modern Times is that in addition to being one of Chaplin's preachiest, it's also one of his funniest, and humor covers a multitude of polemics. More so than a lot of Chaplin, Modern Times (particularly in its famous factory scenes) is built around elaborate sets and special-effects-driven sequences; the Tramp's tussles with the huge machinery in these sequences of course serve as metaphors of society's exploitation of the lower class, but they are also hilarious, perfectly timed comedy routines. Futility is a concept that shows the intersection of comedy and tragedy perhaps better than any other, and it's a concept on full display here. Entire swatches of humanity are trapped in a cycle that makes their actions and desires futile, and that's tragic. But seeing Chaplin live out that futility? Comedic gold. I should note that, as with most of Chaplin's work, the human genius of Modern Times is that we are laughing with the Tramp, not at him, as Chaplin's trademark empathy gives him a sort of heroism that avoids making him the butt of the joke. I should also note that, while I've spent most of my time talking about the factory and related aspects of the movie, there's an awful lot more to this film that just that. For example, did you know that there is a subplot at one point, the Tramp does cocaine? Yeah, that one was a shocker when I first saw the movie, too.

Insert perfunctory sign-off/don't forget to let me know what you think. Until next time!

If you fancy, you can read the previous post, #s 73-75, here.

Update: The next post, #s 79-81, is up here.

At this point, nothing more than the musings of a restless English teacher on the pop culture he experiences.

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Sunday, July 27, 2014

100 Years...100 Movies 73-75: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Silence of the Lambs, In the Heat of the Night

Hello all! I'm working my way through AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies

list, giving thoughts, analyses, and generally scattered musings on each

one. For more details on the project, you can read the introductory

post here.

Lots of crime in the movies in this post. Yep.

73. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969, George Roy Hill)

Now, this is a fun one. Admittedly, a lot of that has to do with the acting. Paul Newman and Robert Redford are at the height of their movie-starishness, and they have a great dynamic as the titular Butch and Kid (Harry Longabaugh, if you're curious—no, his mother did not name him "Sundance"). Despite being stuck in a quasi-tragic Bonnie-and-Clyde-esque plot, the two look like they're having the times of their lives, and the movie lets them have it. That's the other aspect of this movie's fun: it's playful to the end. I compared its story to Bonnie and Clyde, mainly because of the date of this movie's release and the western-antihero protagonists who, yes, rob banks and get all blow'd up at the end, but that's about where the comparisons end because this film's tone is entirely different than anything Bonnie and Clyde ever does. Well, I should say tones because really, there are more than one. This is a movie that jumps from goofy to serious to ironic to tense with complete disregard of historical accuracy and tonal continuity, which makes it a plucky, energetic film to experience, especially for the first time. If I'm being completely honest, I'm not sure all that pluck ends up justifying some of the film's more dead-end moments, making the movie more uneven than its placement on this list would indicate, and the whole thing often feels more fun than meaningful. But, hey, given that I just praised The Shawshank Redemption for lacking just such Importance, I should have room in my heart for this one, too. And I do. I like it.

74. The Silence of the Lambs (1991, Jonathan Demme)

Okay, so here's another fun one. Yes, I am using that word loosely. The Silence of the Lambs is one of those movies that's kind of weird to call "fun" (I mean, it features not just a cannibal but also a dude who wants to wear women's skins), and that's probably not the right term, but there's no question in my mind that the film's primary MO is to entertain. That's the contradictory thing about so many movies, especially horror movies: they aim to entertain you with emotions that would not normally be entertaining to experience, such as fear (see also: tragedies and their invocation of sorrow). One of the things I love about The Silence of the Lambs is how deftly it navigates that contradiction. Whereas other films, including many of the horror thrillers inspired by Silence's success, are often sadistic, punishing affairs for not just their characters but also their audiences, this movie is often funny and humane in its treatment of the story. Silence also manages to avoid the other major pitfall of the crime genre in that, in spite of having a spirit of fun, it gives the criminal acts the weight they deserve. CSI this is not, and every death in the film have a gravity to it lacking in so many other cinematic criminal acts. It manages to pull off both the fun and the gravity because, like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Silence of the Lambs has an excellent command of tone. In fact, it's pretty much a masterpiece of sustaining a singular tone throughout, which makes this film a remarkably cohesive, mesmerizing one in spite of its perhaps contradictory goals. That gives it an edge over Butch Cassidy in my book, if we're going to compare the films I'm (maybe misguidedly) calling "fun" in this post.

75. *In the Heat of the Night (1967, Norman Jewison)

This is definitely a monumental film. Monumental in the sense that this movie came out in '67 not only starring a black actor (no less than top billing, too!) but also featuring a plot and screenplay that depict with uncompromising condemnation the vicious racism of the then-contemporary American South. Heck, a movie like this would be monumental in 2014, too, which, sorry folks, is just disgraceful. Think about it: how many recent movies have seriously taken to task the racial strife in modern-day America and more specifically, the modern South? We've got plenty of films like The Help and 12 Years a Slave that loudly (and in The Help's case, perhaps arrogantly) proclaim that golly, our society sure used to be racist, but films that examine contemporary racism? Those are few and far between, and hotly contested when they do come around (just look at the embarrassing attacks that greeted Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing upon its release). All that is to say that yes, I acknowledge the historical importance of In the Heat of the Night. Now, in addition to being historically significant, is In the Heat of the Night a "good" movie? I'd say it is, though if I may split hairs, I'd have to say that is isn't a "very good" movie (and certainly not a "great" one). First, the good: Sydney Poitier and Rod Steiger are both fantastic, and they have a cool buddy-cop chemistry, the texture of which also does a lot to "show don't tell" the racial politics of the town. It's also a fairly spritely, exciting movie, with consistent action beats and that boring character development thingy mostly relegated to small moments that don't detract from the overall momentum. The bad: the character development, for one. Poitier and Steiger's characters are still good (if a bit broadly drawn), but hoo wee, the rest of the cast is stuck with the paper-thinnest of stock characters solely in service of the plot. And speaking of the plot, the mystery (the, ahem, "murder on their hands they don't know what to do with") isn't all that great. Not to give anything away, but it's way too dependent on some pieces of information that we get a scant half hour from the movie's end, so much so that I feel like it's jerking me around, and it's not even that cool of a reveal anyway. The film is also mostly rote, visually, though I suppose it could have looked a lot more interesting back in the late '60s. Who knows? Anyway, not a waste of time, but not, I think, an all-time classic either.

And I'm now officially seventy-five percent done with this list! Woo hoo! Let me know what you think of these movies. Until next time!

You can read the previous post, #s 70-72, here.

Update: You can read ahead to the next post, #s 76-78, here.

Lots of crime in the movies in this post. Yep.

73. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969, George Roy Hill)

Now, this is a fun one. Admittedly, a lot of that has to do with the acting. Paul Newman and Robert Redford are at the height of their movie-starishness, and they have a great dynamic as the titular Butch and Kid (Harry Longabaugh, if you're curious—no, his mother did not name him "Sundance"). Despite being stuck in a quasi-tragic Bonnie-and-Clyde-esque plot, the two look like they're having the times of their lives, and the movie lets them have it. That's the other aspect of this movie's fun: it's playful to the end. I compared its story to Bonnie and Clyde, mainly because of the date of this movie's release and the western-antihero protagonists who, yes, rob banks and get all blow'd up at the end, but that's about where the comparisons end because this film's tone is entirely different than anything Bonnie and Clyde ever does. Well, I should say tones because really, there are more than one. This is a movie that jumps from goofy to serious to ironic to tense with complete disregard of historical accuracy and tonal continuity, which makes it a plucky, energetic film to experience, especially for the first time. If I'm being completely honest, I'm not sure all that pluck ends up justifying some of the film's more dead-end moments, making the movie more uneven than its placement on this list would indicate, and the whole thing often feels more fun than meaningful. But, hey, given that I just praised The Shawshank Redemption for lacking just such Importance, I should have room in my heart for this one, too. And I do. I like it.

74. The Silence of the Lambs (1991, Jonathan Demme)

Okay, so here's another fun one. Yes, I am using that word loosely. The Silence of the Lambs is one of those movies that's kind of weird to call "fun" (I mean, it features not just a cannibal but also a dude who wants to wear women's skins), and that's probably not the right term, but there's no question in my mind that the film's primary MO is to entertain. That's the contradictory thing about so many movies, especially horror movies: they aim to entertain you with emotions that would not normally be entertaining to experience, such as fear (see also: tragedies and their invocation of sorrow). One of the things I love about The Silence of the Lambs is how deftly it navigates that contradiction. Whereas other films, including many of the horror thrillers inspired by Silence's success, are often sadistic, punishing affairs for not just their characters but also their audiences, this movie is often funny and humane in its treatment of the story. Silence also manages to avoid the other major pitfall of the crime genre in that, in spite of having a spirit of fun, it gives the criminal acts the weight they deserve. CSI this is not, and every death in the film have a gravity to it lacking in so many other cinematic criminal acts. It manages to pull off both the fun and the gravity because, like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Silence of the Lambs has an excellent command of tone. In fact, it's pretty much a masterpiece of sustaining a singular tone throughout, which makes this film a remarkably cohesive, mesmerizing one in spite of its perhaps contradictory goals. That gives it an edge over Butch Cassidy in my book, if we're going to compare the films I'm (maybe misguidedly) calling "fun" in this post.

75. *In the Heat of the Night (1967, Norman Jewison)

This is definitely a monumental film. Monumental in the sense that this movie came out in '67 not only starring a black actor (no less than top billing, too!) but also featuring a plot and screenplay that depict with uncompromising condemnation the vicious racism of the then-contemporary American South. Heck, a movie like this would be monumental in 2014, too, which, sorry folks, is just disgraceful. Think about it: how many recent movies have seriously taken to task the racial strife in modern-day America and more specifically, the modern South? We've got plenty of films like The Help and 12 Years a Slave that loudly (and in The Help's case, perhaps arrogantly) proclaim that golly, our society sure used to be racist, but films that examine contemporary racism? Those are few and far between, and hotly contested when they do come around (just look at the embarrassing attacks that greeted Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing upon its release). All that is to say that yes, I acknowledge the historical importance of In the Heat of the Night. Now, in addition to being historically significant, is In the Heat of the Night a "good" movie? I'd say it is, though if I may split hairs, I'd have to say that is isn't a "very good" movie (and certainly not a "great" one). First, the good: Sydney Poitier and Rod Steiger are both fantastic, and they have a cool buddy-cop chemistry, the texture of which also does a lot to "show don't tell" the racial politics of the town. It's also a fairly spritely, exciting movie, with consistent action beats and that boring character development thingy mostly relegated to small moments that don't detract from the overall momentum. The bad: the character development, for one. Poitier and Steiger's characters are still good (if a bit broadly drawn), but hoo wee, the rest of the cast is stuck with the paper-thinnest of stock characters solely in service of the plot. And speaking of the plot, the mystery (the, ahem, "murder on their hands they don't know what to do with") isn't all that great. Not to give anything away, but it's way too dependent on some pieces of information that we get a scant half hour from the movie's end, so much so that I feel like it's jerking me around, and it's not even that cool of a reveal anyway. The film is also mostly rote, visually, though I suppose it could have looked a lot more interesting back in the late '60s. Who knows? Anyway, not a waste of time, but not, I think, an all-time classic either.

And I'm now officially seventy-five percent done with this list! Woo hoo! Let me know what you think of these movies. Until next time!

You can read the previous post, #s 70-72, here.

Update: You can read ahead to the next post, #s 76-78, here.

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

100 Years...100 Movies 70-72: A Clockwork Orange, Saving Private Ryan, The Shawshank Redemption

Hello all! I'm working my way through AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies

list, giving thoughts, analyses, and generally scattered musings on each

one. For more details on the project, you can read the introductory

post here.

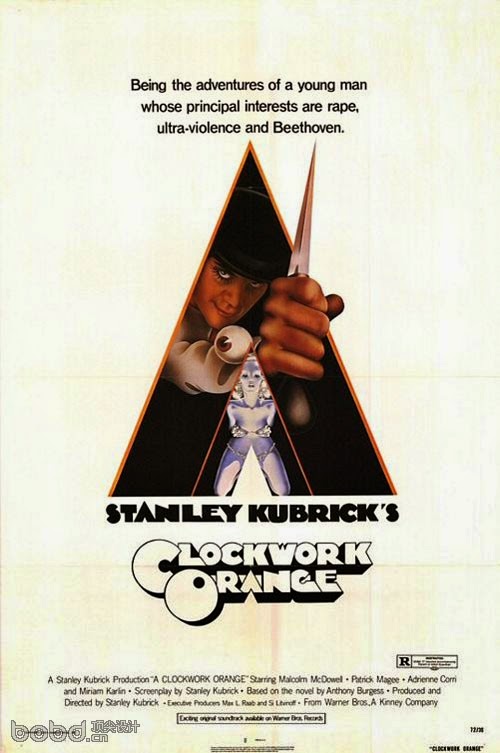

So, this post includes the second (and last) of the Stanley Kubrick movies on this list, and as with 2001, I'm less than thrilled with it, although I do like it better than that original film. Why oh why couldn't AFI actually pick the Kubrick films that I actually like? Anyway, all that is to say that I'm sorry for the overlong writeup of A Clockwork Orange. Hope the mostly reasonable length of the other two entries makes it okay.

70. *A Clockwork Orange (1971, Stanley Kubrick)

This movie is such a mess that I'm struggling to find a good starting point for this discussion. It's not so much "bad" as poorly calculated, so I guess I might as well begin there, especially considering that Stanley Kubrick is one of the most calculating movie directors of all time. And that's not a bad thing! This being a Kubrick film, of course, A Clockwork Orange is a technical masterpiece, full of inventive camerawork, striking imagery, and some of the coolest frame compositions out there. The thing is, as I see it, that technical mastery is also what causes one of the film's biggest problems: it's intentionally filmed as a comedy [1], which of course begs the question of whether or not such a plot as this one (one, in case this work's reputation has eluded you, that is chock full of beatings, rape, torture, and grotequery) should be filmed as a comedy. That question gets into the whole issue of whether there are any subjects off-limits to humor, an issue I don't feel equipped to weigh in on, but I will say this: the jauntiness of the proceedings makes it terrifically difficult for me to figure out what to do with the film's violence. I have no doubt that Kubrick intends for this film to be against rape and gang violence, but it's also possible for there to be miles between authorial intent and actual effect. To be sure, Alex's leering gaze in the first shot makes it clear that our protagonist is as much villain as audience surrogate (though, troublingly, he's also that in the prison and rehabilitation sequences); that being said, there's also something undeniably seductive about the way the violence is situated from Alex's (often joking) perspective, a calculated choice that Kubrick has made to no doubt show the depravity of the character, but a calculation that also hinges so much of its impact on assumptions about the psyche of his viewers that I really think the power of those scenes has fumbled from the filmmakers' control. There's also the problem that many of Kubrick's choices in those scenes, even the more effective ones, often involve objectifying the (mostly female) victims [2]. I do recognize that this film is a satire and that this objectification often serves the satirical points of the film quite well (esp. in reflecting the effects of the hypersexualized society in which Alex lives), but objectification for a purpose is objectification nonetheless, and by gum, when you're dealing with victims of rape, I'm not sure if objectification should be on the table at all. I'm getting rambly, so let me close out by saying that I might be more charitable toward the unintended consequences of the satire if I had a feeling that the satire were serving a larger social point beyond pure nihilism, but I just don't think that's the case. The film, for all its unintended effects, does not want to be on Alex's side, but neither does it want to be on any other side or take any position at all, it seems, given the horrific (and often parodic) nature of the government's penal system. It's a movie that wants to be somehow against both criminal behavior and criminal rehabilitation. At its most constructive, it seems to say that individual autonomy is more important than morality [3], but even then, I'm hesitant to assign that interpretation for all the contradictions it makes in the movie as a whole. So again, it's not a bad movie (it's far too technically accomplished and smart for that), just one that seems horribly (dangerously?) messy to me.

71. Saving Private Ryan (1998, Steven Spielberg)

After the overlong response for A Clockwork Orange (sorrynotsorry, folks), I'll be brief here. The common critical narrative on Saving Private Ryan has become that it's a great movie in its opening Beaches of Normandy sequence and merely an okay movie for the other two hours of its duration. And, boringly, my opinion is basically just a variation on that idea. The first thirty minutes of the film are some of the most visceral, terrifying, and effectively anti-war war movie minutes ever put to film. It turns World War II (our "righteous" war, let's not forget) into the chaotic horror film that I feel most cinematic battle scenes should be. War is hell, goes the banality, and Saving Private Ryan's storming of the beaches is one of cinema's most hellish, with imagery right out of Dante's Inferno (or, you know, real life, which war movies are all too good at letting us forget). The rest of the movie, I have to agree with the critics, is pretty by-the-numbers, as far as war movies go, and it leans a little too hard on the stop-being-a-coward-and-be-a-man-and-kill-people ethic that rubs me wrong about some other war movies. That being said, I do think that in the final fifteen-or-so minutes, the film becomes near-great again, building to a powerful climax with the (spoilers) sacrifice of Tom Hanks's character [4]. So there's that. Yeah, overall, a movie I like with a few essential scenes, but so many other films in just Spielberg's filmography alone deserve this spot, so whatever.

72. The Shawshank Redemption (1994, Frank Darabont)

Well, what a nice surprise. I've spent a good deal of time poring over this AFI list, even before beginning this project (because, you know, I'm a horrible nerd for these sorts of things, which I realize is a bad habit and I should feel bad), but until preparing for this post, I had completely forgotten that The Shawshank Redemption was on this list. What's wonderful about that for me is that the movie is such a non-AFI movie, by which I mean that there is next to nothing Important about it. It's not the work of a so-called "auteur" like Kubrick or even that of generally well-regarded director like Spielberg; Darabont is, in fact, primarily known for directing inoffensive adaptations of Stephen King's work, which is about as glorious a populist legacy as I can envision. There's nothing particularly innovative about its cinematography, either. It's not a movie driven by Big Important Actors like Marlon Brando or Orson Welles playing self-important roles; the acting in Shawshank is top-notch, of course, but it's of the smaller, warmer variety that tends not to get lots of attention from the codifiers of Hollywood history. It's also not a movie with Big Social Themes; although it's set in a prison, the film (along with the Stephen King novella it's based on) has almost zero interest in saying anything socially relevant about the state of incarceration in the United States in the mid-20th century or in contemporary times or ever (compare that, for example, to A Clockwork Orange's hyper social awareness). No, more than anything, The Shawshank Redemption just wants to give its audience a fun, feel-good time. That's a mission statement sorely lacking from so many of the dramas on this list. Now, as I'm sure you can tell from some of the other posts in this project, I love me some self-important dramas, but the idea that films with weighty themes and historical significance are the only films worth honoring is so toxic to cinema culture that it's a genuine relief to me that something like The Shawshank Redemption (an antidote to that toxicity if there ever was one) has gathered enough critical inertia over the years and years of cable reruns to emerge on this list.

Agree with my takes on these movies? Disagree? I'd in particular love to hear someone call me out on my ideas about A Clockwork Orange, as I'm still very conflicted about the film. Or you could call me out on what I have to say about these other movies, too. It's all good.

Until next time!

If you want, you can go back and read the previous post, #s 67-69, here.

Update: The next post, #s 73-75, is right here.

1] There are a lot of indications that A Clockwork Orange is a formally comedic work, but the two main elements that I would cite are the abundance of wide-angle distortions (a technique often used to frame silliness) and the carnivalesque direction of the acting, both of which exaggerate the onscreen images to a somewhat humorous effect.

2] The first rape (the one Alex and his droods walk in on at the beginning) is a good example of what I'm talking about. The film is definitely indicting Alex's callous attitude toward the woman, but it's also a scene in which the depiction of the violence is bloodless enough to sort of emphasize the nakedness of the woman more than the violence itself, which again is keeping with Alex's perspective, but that's a mighty irresponsible stance for a film to take, even for the purpose of satire.

3] Which, again, I think is sort of an irresponsible and sloppy message to ground satire in, especially when the film adaptation lacks the (admittedly clumsy) final chapter of the original novel, in which Alex discovers that the purpose of that autonomy is to develop a moral awareness.

4] You know what bugs the heck out of me, though? That the death of Tom Hanks's character totally messes of the POV of the movie! Like, the whole film leads you on to believe that it's an elderly Tom Hanks in the graveyard at the beginning remembering all this stuff, and as a result, the whole movie is set in Hanks's perspective—only then it turns out that this isn't Hanks's memory at all because he's dead, so how on earth did we just remember everything from his POV?? It drives me nuts.

So, this post includes the second (and last) of the Stanley Kubrick movies on this list, and as with 2001, I'm less than thrilled with it, although I do like it better than that original film. Why oh why couldn't AFI actually pick the Kubrick films that I actually like? Anyway, all that is to say that I'm sorry for the overlong writeup of A Clockwork Orange. Hope the mostly reasonable length of the other two entries makes it okay.

70. *A Clockwork Orange (1971, Stanley Kubrick)

This movie is such a mess that I'm struggling to find a good starting point for this discussion. It's not so much "bad" as poorly calculated, so I guess I might as well begin there, especially considering that Stanley Kubrick is one of the most calculating movie directors of all time. And that's not a bad thing! This being a Kubrick film, of course, A Clockwork Orange is a technical masterpiece, full of inventive camerawork, striking imagery, and some of the coolest frame compositions out there. The thing is, as I see it, that technical mastery is also what causes one of the film's biggest problems: it's intentionally filmed as a comedy [1], which of course begs the question of whether or not such a plot as this one (one, in case this work's reputation has eluded you, that is chock full of beatings, rape, torture, and grotequery) should be filmed as a comedy. That question gets into the whole issue of whether there are any subjects off-limits to humor, an issue I don't feel equipped to weigh in on, but I will say this: the jauntiness of the proceedings makes it terrifically difficult for me to figure out what to do with the film's violence. I have no doubt that Kubrick intends for this film to be against rape and gang violence, but it's also possible for there to be miles between authorial intent and actual effect. To be sure, Alex's leering gaze in the first shot makes it clear that our protagonist is as much villain as audience surrogate (though, troublingly, he's also that in the prison and rehabilitation sequences); that being said, there's also something undeniably seductive about the way the violence is situated from Alex's (often joking) perspective, a calculated choice that Kubrick has made to no doubt show the depravity of the character, but a calculation that also hinges so much of its impact on assumptions about the psyche of his viewers that I really think the power of those scenes has fumbled from the filmmakers' control. There's also the problem that many of Kubrick's choices in those scenes, even the more effective ones, often involve objectifying the (mostly female) victims [2]. I do recognize that this film is a satire and that this objectification often serves the satirical points of the film quite well (esp. in reflecting the effects of the hypersexualized society in which Alex lives), but objectification for a purpose is objectification nonetheless, and by gum, when you're dealing with victims of rape, I'm not sure if objectification should be on the table at all. I'm getting rambly, so let me close out by saying that I might be more charitable toward the unintended consequences of the satire if I had a feeling that the satire were serving a larger social point beyond pure nihilism, but I just don't think that's the case. The film, for all its unintended effects, does not want to be on Alex's side, but neither does it want to be on any other side or take any position at all, it seems, given the horrific (and often parodic) nature of the government's penal system. It's a movie that wants to be somehow against both criminal behavior and criminal rehabilitation. At its most constructive, it seems to say that individual autonomy is more important than morality [3], but even then, I'm hesitant to assign that interpretation for all the contradictions it makes in the movie as a whole. So again, it's not a bad movie (it's far too technically accomplished and smart for that), just one that seems horribly (dangerously?) messy to me.

71. Saving Private Ryan (1998, Steven Spielberg)

After the overlong response for A Clockwork Orange (sorrynotsorry, folks), I'll be brief here. The common critical narrative on Saving Private Ryan has become that it's a great movie in its opening Beaches of Normandy sequence and merely an okay movie for the other two hours of its duration. And, boringly, my opinion is basically just a variation on that idea. The first thirty minutes of the film are some of the most visceral, terrifying, and effectively anti-war war movie minutes ever put to film. It turns World War II (our "righteous" war, let's not forget) into the chaotic horror film that I feel most cinematic battle scenes should be. War is hell, goes the banality, and Saving Private Ryan's storming of the beaches is one of cinema's most hellish, with imagery right out of Dante's Inferno (or, you know, real life, which war movies are all too good at letting us forget). The rest of the movie, I have to agree with the critics, is pretty by-the-numbers, as far as war movies go, and it leans a little too hard on the stop-being-a-coward-and-be-a-man-and-kill-people ethic that rubs me wrong about some other war movies. That being said, I do think that in the final fifteen-or-so minutes, the film becomes near-great again, building to a powerful climax with the (spoilers) sacrifice of Tom Hanks's character [4]. So there's that. Yeah, overall, a movie I like with a few essential scenes, but so many other films in just Spielberg's filmography alone deserve this spot, so whatever.

72. The Shawshank Redemption (1994, Frank Darabont)

Well, what a nice surprise. I've spent a good deal of time poring over this AFI list, even before beginning this project (because, you know, I'm a horrible nerd for these sorts of things, which I realize is a bad habit and I should feel bad), but until preparing for this post, I had completely forgotten that The Shawshank Redemption was on this list. What's wonderful about that for me is that the movie is such a non-AFI movie, by which I mean that there is next to nothing Important about it. It's not the work of a so-called "auteur" like Kubrick or even that of generally well-regarded director like Spielberg; Darabont is, in fact, primarily known for directing inoffensive adaptations of Stephen King's work, which is about as glorious a populist legacy as I can envision. There's nothing particularly innovative about its cinematography, either. It's not a movie driven by Big Important Actors like Marlon Brando or Orson Welles playing self-important roles; the acting in Shawshank is top-notch, of course, but it's of the smaller, warmer variety that tends not to get lots of attention from the codifiers of Hollywood history. It's also not a movie with Big Social Themes; although it's set in a prison, the film (along with the Stephen King novella it's based on) has almost zero interest in saying anything socially relevant about the state of incarceration in the United States in the mid-20th century or in contemporary times or ever (compare that, for example, to A Clockwork Orange's hyper social awareness). No, more than anything, The Shawshank Redemption just wants to give its audience a fun, feel-good time. That's a mission statement sorely lacking from so many of the dramas on this list. Now, as I'm sure you can tell from some of the other posts in this project, I love me some self-important dramas, but the idea that films with weighty themes and historical significance are the only films worth honoring is so toxic to cinema culture that it's a genuine relief to me that something like The Shawshank Redemption (an antidote to that toxicity if there ever was one) has gathered enough critical inertia over the years and years of cable reruns to emerge on this list.

Agree with my takes on these movies? Disagree? I'd in particular love to hear someone call me out on my ideas about A Clockwork Orange, as I'm still very conflicted about the film. Or you could call me out on what I have to say about these other movies, too. It's all good.

Until next time!

If you want, you can go back and read the previous post, #s 67-69, here.

Update: The next post, #s 73-75, is right here.

1] There are a lot of indications that A Clockwork Orange is a formally comedic work, but the two main elements that I would cite are the abundance of wide-angle distortions (a technique often used to frame silliness) and the carnivalesque direction of the acting, both of which exaggerate the onscreen images to a somewhat humorous effect.

2] The first rape (the one Alex and his droods walk in on at the beginning) is a good example of what I'm talking about. The film is definitely indicting Alex's callous attitude toward the woman, but it's also a scene in which the depiction of the violence is bloodless enough to sort of emphasize the nakedness of the woman more than the violence itself, which again is keeping with Alex's perspective, but that's a mighty irresponsible stance for a film to take, even for the purpose of satire.

3] Which, again, I think is sort of an irresponsible and sloppy message to ground satire in, especially when the film adaptation lacks the (admittedly clumsy) final chapter of the original novel, in which Alex discovers that the purpose of that autonomy is to develop a moral awareness.

4] You know what bugs the heck out of me, though? That the death of Tom Hanks's character totally messes of the POV of the movie! Like, the whole film leads you on to believe that it's an elderly Tom Hanks in the graveyard at the beginning remembering all this stuff, and as a result, the whole movie is set in Hanks's perspective—only then it turns out that this isn't Hanks's memory at all because he's dead, so how on earth did we just remember everything from his POV?? It drives me nuts.

Tuesday, July 22, 2014

100 Years...100 Movies 67-69: Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Unforgiven, Tootsie

Hello all! I'm working my way through AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies

list, giving thoughts, analyses, and generally scattered musings on each

one. For more details on the project, you can read the introductory

post here.

More AFI, y'all. Read on.

67. *Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966, Mike Nichols)

Upon first seeing Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (about 11 pm Sunday night, if you're curious), I was struck by what seem to me as the two most major aspects of historical import in this very historically important film. First of all (and this is something that has been noted time and time again), it's a tremendously taboo-breaking film, one of the first American films to include with such frequency the depths (or heights, I suppose, depending on your position) of profanity such as "goddamn" and "Christ," as well as a few phrases that have become a little more PG than R-rated in the near-fifty years since the film's release (for instance, um, "hump the hostess"). As I've said before, though, taboo-breaking is a meaningless (even irritating) action without some kind of philosophical or aesthetic purpose behind it, which is why I'm much more interested in what I see as the second major historical innovation of this film, which is that it's one of the first American films that appears steeped in an acute awareness of world cinema. My first idea for this writeup had something to do with comparing Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? to the works of Ingmar Bergman, and although I'll admit that that idea probably came from dwelling on the obvious signifiers (marital strife, black & white cinematography, connections to stage drama) without actually analyzing anything deeper (there's got to be some significance to the fact that Woolf's camera is way busier than Bergman would have ever allowed), that I even thought to make that comparison at all speaks volumes about how strikingly different the craft of Woolf is from any of the other pre-'70s films on this list. In that regard, this film feels like a true ground-zero for New American Cinema. As for the content of the film beyond the craft, I did find it a tad bit overwrought for my tastes [1], particularly in the early goings, where the characters are introduced with turned-to-11 emotions. Still, there's no denying that the intensity builds to a baroque beauty by the third act. And as long as there's beauty, I can make peace with an awful lot of flaws.

68. Unforgiven (1992, Clint Eastwood)

And speaking of beauty, mother of Spielberg! this movie has spades of it. One of the central premises of Unforgiven is that time-honored film tradition of using gorgeous cinematography to stage brutal violence. It's a technique that pretty much made the careers of Joel and Ethan Coen (although yes, I know that they don't only make brutally violent movies), and it serves Clint Eastwood and cinematographer Jack Green tremendously here. Cinematography aside, Unforgiven's other central premise is to be a sort of anti-western, pretty much the anti-True Grit, in fact (which was itself a kind of anti-western—there's like... layers, man). Like True Grit, Unforgiven features an aging gunslinger (played in both cases by actors who are themselves in the post-gunslinging end of their career) thrust into the young man's game of a traditional western scenario, and in doing so the man must not only confront his own mortality but also the death of the gunslinging way of life in society[2]. The different is that whereas True Grit is a funny, fist-pumping sort of send up of western tropes, characterized of course by the lackadaisical John Wayne, Unforgiven gives the western the long, cold Clint Eastwood stare, and by golly, that stare doesn't let up for fun send-uppery. The western has been declared dead so many times that it's accumulated quite its share of elegies, but for me, Unforgiven will always be the definitive one. It's a stark, uncompromising work that gazes into the abyss with an intensity that few movies of any genre do. One of the best, for sure.

69. Tootsie (1982, Sydney Pollack)

Fun fact about this AFI list: the most represented subgenre of comedy behind the romantic comedy is the gender-bending comedy [3], which tells me two things: first, that there needs to be more comedies on this list, and second, that yeah, gender-bending comedies can be freaking funny when they're done right. And boy, can they be done wrong; for every Some Like It Hot in Hollywood's history are at least three White Chicks, which, believe me, is an awful thing to foist on the world. And maybe Some Like It Hot is part of the problem, given that the majority of the genre's worst offenders end up taking that earlier film's only-joking-stakes approach, where everything is a joke. That approach wouldn't be so bad if those movies were half as funny as Some Like It Hot, but more often than not they end up being not only laughless and dull but also irritatingly gender normative (an especially disappointing characteristic considering Some Like It Hot's freewheeling take on gender). Tootsie, on the other hand (yes, I still remember that I'm supposed to be talking about this movie), takes pretty much the opposite approach to Some Like It Hot's jokiness. Don't get me wrong; Tootsie is plenty hilarious. But unlike its predecessor, Tootsie is also a serious study of the social forces influencing gender, particularly those that affect females in the workplace. As in Some Like It Hot, the protagonist (here Dustin Hoffman) accumulates would-be male suitors while dressed as a woman at work, but instead of the sweet-but-idiotic-but-mostly-harmless-anyway fellow that pines for Jack Lemmon, Hoffman's Dorothy is warned that a fellow male actor is known by the women on-set as "The Tongue," so named for his aggressively invasive behavior when acting out scripted kisses. It's a joke and a funny one at that, but there's also an undercurrent of darkness in that moment that is indicative of the more straight-faced subtext of the film. It's a very funny movie, but it's also one that wants to use its laughs to say something meaningful about the human experience.

And that's that. Let me know what you think. Until next time!

If you want, you can read the previous entry, #s 64-66, here.

Update: The next post, #s 70-72, is up here.

1] I haven't, by the way, read or seen the play this movie is based on, although if Wikipedia is to be trusted, it's not all that different from what I saw in the film.

2] Or at least in the fantasy society in which the gunslinger archetype actually exists. Which, thankfully, is mostly mythical, although I do mourn that the phrase "This town ain't big enough for the two of us" was almost certainly never used in a real-life context.

3] Most of which are romantic comedies, too, so maybe that's not the most interesting fact after all.

More AFI, y'all. Read on.

67. *Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966, Mike Nichols)

Upon first seeing Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (about 11 pm Sunday night, if you're curious), I was struck by what seem to me as the two most major aspects of historical import in this very historically important film. First of all (and this is something that has been noted time and time again), it's a tremendously taboo-breaking film, one of the first American films to include with such frequency the depths (or heights, I suppose, depending on your position) of profanity such as "goddamn" and "Christ," as well as a few phrases that have become a little more PG than R-rated in the near-fifty years since the film's release (for instance, um, "hump the hostess"). As I've said before, though, taboo-breaking is a meaningless (even irritating) action without some kind of philosophical or aesthetic purpose behind it, which is why I'm much more interested in what I see as the second major historical innovation of this film, which is that it's one of the first American films that appears steeped in an acute awareness of world cinema. My first idea for this writeup had something to do with comparing Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? to the works of Ingmar Bergman, and although I'll admit that that idea probably came from dwelling on the obvious signifiers (marital strife, black & white cinematography, connections to stage drama) without actually analyzing anything deeper (there's got to be some significance to the fact that Woolf's camera is way busier than Bergman would have ever allowed), that I even thought to make that comparison at all speaks volumes about how strikingly different the craft of Woolf is from any of the other pre-'70s films on this list. In that regard, this film feels like a true ground-zero for New American Cinema. As for the content of the film beyond the craft, I did find it a tad bit overwrought for my tastes [1], particularly in the early goings, where the characters are introduced with turned-to-11 emotions. Still, there's no denying that the intensity builds to a baroque beauty by the third act. And as long as there's beauty, I can make peace with an awful lot of flaws.

68. Unforgiven (1992, Clint Eastwood)

And speaking of beauty, mother of Spielberg! this movie has spades of it. One of the central premises of Unforgiven is that time-honored film tradition of using gorgeous cinematography to stage brutal violence. It's a technique that pretty much made the careers of Joel and Ethan Coen (although yes, I know that they don't only make brutally violent movies), and it serves Clint Eastwood and cinematographer Jack Green tremendously here. Cinematography aside, Unforgiven's other central premise is to be a sort of anti-western, pretty much the anti-True Grit, in fact (which was itself a kind of anti-western—there's like... layers, man). Like True Grit, Unforgiven features an aging gunslinger (played in both cases by actors who are themselves in the post-gunslinging end of their career) thrust into the young man's game of a traditional western scenario, and in doing so the man must not only confront his own mortality but also the death of the gunslinging way of life in society[2]. The different is that whereas True Grit is a funny, fist-pumping sort of send up of western tropes, characterized of course by the lackadaisical John Wayne, Unforgiven gives the western the long, cold Clint Eastwood stare, and by golly, that stare doesn't let up for fun send-uppery. The western has been declared dead so many times that it's accumulated quite its share of elegies, but for me, Unforgiven will always be the definitive one. It's a stark, uncompromising work that gazes into the abyss with an intensity that few movies of any genre do. One of the best, for sure.

69. Tootsie (1982, Sydney Pollack)

Fun fact about this AFI list: the most represented subgenre of comedy behind the romantic comedy is the gender-bending comedy [3], which tells me two things: first, that there needs to be more comedies on this list, and second, that yeah, gender-bending comedies can be freaking funny when they're done right. And boy, can they be done wrong; for every Some Like It Hot in Hollywood's history are at least three White Chicks, which, believe me, is an awful thing to foist on the world. And maybe Some Like It Hot is part of the problem, given that the majority of the genre's worst offenders end up taking that earlier film's only-joking-stakes approach, where everything is a joke. That approach wouldn't be so bad if those movies were half as funny as Some Like It Hot, but more often than not they end up being not only laughless and dull but also irritatingly gender normative (an especially disappointing characteristic considering Some Like It Hot's freewheeling take on gender). Tootsie, on the other hand (yes, I still remember that I'm supposed to be talking about this movie), takes pretty much the opposite approach to Some Like It Hot's jokiness. Don't get me wrong; Tootsie is plenty hilarious. But unlike its predecessor, Tootsie is also a serious study of the social forces influencing gender, particularly those that affect females in the workplace. As in Some Like It Hot, the protagonist (here Dustin Hoffman) accumulates would-be male suitors while dressed as a woman at work, but instead of the sweet-but-idiotic-but-mostly-harmless-anyway fellow that pines for Jack Lemmon, Hoffman's Dorothy is warned that a fellow male actor is known by the women on-set as "The Tongue," so named for his aggressively invasive behavior when acting out scripted kisses. It's a joke and a funny one at that, but there's also an undercurrent of darkness in that moment that is indicative of the more straight-faced subtext of the film. It's a very funny movie, but it's also one that wants to use its laughs to say something meaningful about the human experience.

And that's that. Let me know what you think. Until next time!

If you want, you can read the previous entry, #s 64-66, here.

Update: The next post, #s 70-72, is up here.

1] I haven't, by the way, read or seen the play this movie is based on, although if Wikipedia is to be trusted, it's not all that different from what I saw in the film.

2] Or at least in the fantasy society in which the gunslinger archetype actually exists. Which, thankfully, is mostly mythical, although I do mourn that the phrase "This town ain't big enough for the two of us" was almost certainly never used in a real-life context.

3] Most of which are romantic comedies, too, so maybe that's not the most interesting fact after all.

Thursday, July 17, 2014

100 Years...100 Movies 64-66: Network, The African Queen, Raiders of the Lost Ark

Hello all! I'm working my way through AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies

list, giving thoughts, analyses, and generally scattered musings on each

one. For more details on the project, you can read the introductory

post here.

...in which I can't think of any introduction whatsoever. So...

64. Network (1976, Sidney Lumet)

It's been said before, but I'll say it again because I remain amazed: Network is an astoundingly prescient film, one that even borders on prophetic. I mean, get this: Network not only predicts the rise of both reality TV and the 24-hour news cycle at least a decade before either was a major cultural force, it also understands these future trends deeply enough to critique the exploitation that runs rampant in each creation. Even in 2014, Network is still a relevant, wicked-sharp media satire, which is incredible considering that the major targets of its satire didn't even exist in 1976 [1]. All that prescience wouldn't wouldn't be worth nearly as much, though, if the movie weren't also hilarious and fantastically acted, two characteristics that go hand-in-hand. Network won three of the four acting categories at the Academy Awards (Fay Dunaway, Peter Finch, and Beatrice Straight), and it probably should have won a fourth for William Holden's performance if that had been possible (Finch and Holden were both nominated in the same category, Best Actor). It's loud, showy acting through-and-though, but goshdarnit, it works. I can't stress enough how much the acting helps to turn what is really a bitter, caustic, ugly movie into one of the funniest comedies in American film history. Even so, Network is angry, shrill, and more than a little smug, and I can see how that did (and still does) turn people off—heck, I usually baulk against this sort of "television is the demise of civilization" tirade, because come on, there's a lot of great, intelligent, socially valuable TV out there, and that was true in the '70s, too [2]. And yet, for all the self-congratulatory airs of Network, there's still something pure about the righteous anger on display, pure enough that it sucks me in every time and reminds me that yes, this hatred of the disgusting reality of the media cycle is the reason why Network is one of my favorite movies ever.

65. *The African Queen (1951, John Huston)

For as long as The African Queen sat dormant on my Netflix queue, I had assumed that the film was a serious movie, the sort of straight-laced drama that tends to have Big Themes and attract Academy Awards, the kind of movie that's often kind of a bore to watch outside of the original cultural moment that birthed it. I'm not quite sure why I thought this (although its presence on both iterations of the AFI list surely bolstered this assumption of mine), and as it turns out, I was dead wrong. The African Queen is nuts. I mean, there's barely a serious bone in its cinematic body; to put it in perspective, I'm about to (sort of) discuss Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Raiders, with all its winking and exploding of heads, is only slightly sillier than The African Queen, as far as its prioritizing of swashbuckling over serious ideas (and realism) goes. No archaeologists-as-Errol-Flynn here, though; in The African Queen, the hero is clearly Katharine Hepburn's Rose Sayer, a Methodist missionary-turned-war-monger who, after her brother dies in the aftermath of a WWI-era German attack on their African village, becomes intent on turning the riverboat of friendly neighborhood captain Charlie Allnut (Humphrey Bogart) into a makeshift torpedo to blow the Germans' boat to kingdom come. Yeah, we're definitely not in the land of self-serious Hollywood. And that's not a criticism whatsoever. The African Queen is lots of fun, with both Hepburn and Bogart delivering charming performances. A welcome surprise of a film for me.

66. Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981, Steven Spielberg)

You know, sometimes it's kinda hard to write about my favorite movies. Like, I'm not talking about writing about movies I merely love—if anything, this series has shown that I can yammer on for hundreds of words on movies I love. I mean those movies that have been a part of my life since childhood, movies I internalized deeply before I even knew what film criticism was. Maybe I'm too close to these movies to consistently find analytical footholds. Or maybe they are movies that I've already read so much critical discourse about that I'm paralyzed by the possibility of repeating those critics. I dunno. All that is to say that I have embarrassingly little to say about Raiders of the Lost Ark, even though it's one of my favorite movies ever. What makes writing about Raiders especially difficult is that it's also one of those movies that has little or no interest in making any sort of real-world point outside the joys of cinema culture itself, which, to be clear, is one of my favorite types of movies, but it also means that discussions are limited to the the purely allusive and technical aspects of the film. "Oh, this is cool because it alludes to x movie from Lucas's childhood," "Spielberg's direction is effective because of its efficiency with space," and the like. Those are valid, important discussions to have, but they aren't always discussions I feel especially equipped to engage in, particularly in the case of Indiana Jones, when the allusions refer to a cinematic form (i.e. adventure serials) whose heyday predates my birth by half a century. So yeah. I'm sorry for the lame "discussion about discussions" thing. I love, love, love this movie so much, but beyond gushing that sentiment, I'm all hot air.

That's all for now, folks! Until next time.

You can read the previous post, #s 61-63, here.

Update: The next post, #s 67-69, can be found here.

1] What's arguably more incredible, though, is that TV media rose (sank?) to the challenge of Network's colossal cynicism by actually making the sort of dreck the film cautions against. In a way, we have nobody but TV itself to thank for the intelligence of Network's screenplay. If television had become some completely high-brow medium in the years since '76, I think it's possible that we'd now dismiss Network as self-satisfied paranoia.

2] That's not to say that there isn't tons of crap out there, too, but overall I tend to prefer my film critiques of television (a dubious genre if there ever was one) to follow the path of Good Night, and Good Luck: TV is a medium with a rich potential, and it's sad that people don't always take advantage of that potential.

...in which I can't think of any introduction whatsoever. So...

64. Network (1976, Sidney Lumet)

It's been said before, but I'll say it again because I remain amazed: Network is an astoundingly prescient film, one that even borders on prophetic. I mean, get this: Network not only predicts the rise of both reality TV and the 24-hour news cycle at least a decade before either was a major cultural force, it also understands these future trends deeply enough to critique the exploitation that runs rampant in each creation. Even in 2014, Network is still a relevant, wicked-sharp media satire, which is incredible considering that the major targets of its satire didn't even exist in 1976 [1]. All that prescience wouldn't wouldn't be worth nearly as much, though, if the movie weren't also hilarious and fantastically acted, two characteristics that go hand-in-hand. Network won three of the four acting categories at the Academy Awards (Fay Dunaway, Peter Finch, and Beatrice Straight), and it probably should have won a fourth for William Holden's performance if that had been possible (Finch and Holden were both nominated in the same category, Best Actor). It's loud, showy acting through-and-though, but goshdarnit, it works. I can't stress enough how much the acting helps to turn what is really a bitter, caustic, ugly movie into one of the funniest comedies in American film history. Even so, Network is angry, shrill, and more than a little smug, and I can see how that did (and still does) turn people off—heck, I usually baulk against this sort of "television is the demise of civilization" tirade, because come on, there's a lot of great, intelligent, socially valuable TV out there, and that was true in the '70s, too [2]. And yet, for all the self-congratulatory airs of Network, there's still something pure about the righteous anger on display, pure enough that it sucks me in every time and reminds me that yes, this hatred of the disgusting reality of the media cycle is the reason why Network is one of my favorite movies ever.

65. *The African Queen (1951, John Huston)

For as long as The African Queen sat dormant on my Netflix queue, I had assumed that the film was a serious movie, the sort of straight-laced drama that tends to have Big Themes and attract Academy Awards, the kind of movie that's often kind of a bore to watch outside of the original cultural moment that birthed it. I'm not quite sure why I thought this (although its presence on both iterations of the AFI list surely bolstered this assumption of mine), and as it turns out, I was dead wrong. The African Queen is nuts. I mean, there's barely a serious bone in its cinematic body; to put it in perspective, I'm about to (sort of) discuss Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Raiders, with all its winking and exploding of heads, is only slightly sillier than The African Queen, as far as its prioritizing of swashbuckling over serious ideas (and realism) goes. No archaeologists-as-Errol-Flynn here, though; in The African Queen, the hero is clearly Katharine Hepburn's Rose Sayer, a Methodist missionary-turned-war-monger who, after her brother dies in the aftermath of a WWI-era German attack on their African village, becomes intent on turning the riverboat of friendly neighborhood captain Charlie Allnut (Humphrey Bogart) into a makeshift torpedo to blow the Germans' boat to kingdom come. Yeah, we're definitely not in the land of self-serious Hollywood. And that's not a criticism whatsoever. The African Queen is lots of fun, with both Hepburn and Bogart delivering charming performances. A welcome surprise of a film for me.

66. Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981, Steven Spielberg)

You know, sometimes it's kinda hard to write about my favorite movies. Like, I'm not talking about writing about movies I merely love—if anything, this series has shown that I can yammer on for hundreds of words on movies I love. I mean those movies that have been a part of my life since childhood, movies I internalized deeply before I even knew what film criticism was. Maybe I'm too close to these movies to consistently find analytical footholds. Or maybe they are movies that I've already read so much critical discourse about that I'm paralyzed by the possibility of repeating those critics. I dunno. All that is to say that I have embarrassingly little to say about Raiders of the Lost Ark, even though it's one of my favorite movies ever. What makes writing about Raiders especially difficult is that it's also one of those movies that has little or no interest in making any sort of real-world point outside the joys of cinema culture itself, which, to be clear, is one of my favorite types of movies, but it also means that discussions are limited to the the purely allusive and technical aspects of the film. "Oh, this is cool because it alludes to x movie from Lucas's childhood," "Spielberg's direction is effective because of its efficiency with space," and the like. Those are valid, important discussions to have, but they aren't always discussions I feel especially equipped to engage in, particularly in the case of Indiana Jones, when the allusions refer to a cinematic form (i.e. adventure serials) whose heyday predates my birth by half a century. So yeah. I'm sorry for the lame "discussion about discussions" thing. I love, love, love this movie so much, but beyond gushing that sentiment, I'm all hot air.

That's all for now, folks! Until next time.

You can read the previous post, #s 61-63, here.

Update: The next post, #s 67-69, can be found here.

1] What's arguably more incredible, though, is that TV media rose (sank?) to the challenge of Network's colossal cynicism by actually making the sort of dreck the film cautions against. In a way, we have nobody but TV itself to thank for the intelligence of Network's screenplay. If television had become some completely high-brow medium in the years since '76, I think it's possible that we'd now dismiss Network as self-satisfied paranoia.

2] That's not to say that there isn't tons of crap out there, too, but overall I tend to prefer my film critiques of television (a dubious genre if there ever was one) to follow the path of Good Night, and Good Luck: TV is a medium with a rich potential, and it's sad that people don't always take advantage of that potential.

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

100 Years...100 Movies 61-63: Sullivan's Travels, American Graffiti, Cabaret

Hello all! I'm working my way through AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies

list, giving thoughts, analyses, and generally scattered musings on each

one. For more details on the project, you can read the introductory

post here.

Another few days, another few AFI movies. Yeah, that's about all I've got for an intro. Move along.

61. Sullivan's Travels (1941, Preston Sturges)

I'll be honest here: it has been a very long time since I last saw Sullivan's Travels. Consequently, this discussion is going to have to be kind of vague on the details of this film. I cannot remember, for instance, if the cinematography or direction is any good (though given that it's Preston Sturges running the show, I'd guess they're both at least functional, if not exemplary), so those are topics I'm going to avoid. What I do remember, however, is the plot. And man, that plot is good. It's not just an engaging, funny, slightly satiric story (although it is all those things); it's a story that has such a potent thematic thrust regarding the filmmaking establishment that its barbs are still poking modern-day Hollywood. It's actually kind of hilarious that this film made it onto the AFI list at all [1], given that Sullivan's Travels is an indictment of the self-serious prestige machine that fuels the Academy Awards, film criticism, and, yes, the American Film Institute. When the film's fictional filmmaker John Sullivan decides that comedies are just as socially valuable as prestigious social dramas with capital T Themes, he might as well be directly addressing this list, which, I remind you, is made up of (not counting musicals) less than 10 percent comedy and about 80 percent prestigious social drama with capital T Themes. Now, I like prestigious films as much as the next guy (and goodness knows I've praised plenty of them on this blog), but there's something sort of rousing to Sullivan's Travels's critique. To quote another film on this list, "Make 'em laugh," dangit!

62. American Graffiti (1973, George Lucas)

In discussing George Lucas, a lot of people focus on Star Wars, which is entirely reasonable considering that the original Star Wars trilogy and especially Episode IV are some of the biggest, most groundbreaking, most culturally significant, most aesthetically successful movies of all time. But what often gets lost in all the galaxy-far-far-away shuffle is poor old American Graffiti, the little movie that immediately precedes Star Wars in Lucas's filmography. And that's kind of too bad because not only is American Graffiti, like Star Wars, a great, distinctively personal film (as well as proof that at one time, George Lucas was actually a good writer), it also is pretty groundbreaking in its own right. The extent to which it incorporates classic rock and soul tunes into its soundtrack was pretty much unheard of at the time of its release, and it remains one of the most technically and thematically sophisticated uses of pop music ever in American cinema. The wall-to-wall-songs approach to its soundtrack has also been hugely influential on subsequent generations of filmmakers—you can bet that Dazed and Confused and Do the Right Thing, to name two of American Graffiti's biggest heirs, would sound a lot different without it. And speaking of those heirs, another piece of American Graffiti's groundbreaking legacy is that it (to my knowledge) pretty much invented the whole cinematic subgenre of wistful coming-of-age stories that take place over a single night. Movies like Sixteen Candles, Superbad, and yes, Dazed and Confused all work within this mode and basically follow the structure of American Graffiti verbatim, with a series of mostly episodic (and mostly comedic) events slowly escalating to catharsis at dawn. It's a killer way to construct a plot, and it's always a treat to see a movie adopt the form. I've talked so much about the influence of American Graffiti that I've run out of room to praise the actual movie itself. Don't let my lack of discussion fool you; American Graffiti is great, and, for what it's worth, I think it's better than at least sixty-seven percent of the Star Wars films. I'm guessing it's pretty obvious which sixty-seven percent.

63. *Cabaret (1972, Bob Fosse)

So this is the kind of musical American filmmakers made in the '70s. You know, for all the movie musicals I've seen (and, for all my tepid feelings toward them, I've seen quite a few), I don't think I've ever watched one from the '70s, unless you count something like The Aristocats, which I don't (and besides, it's rarely the animated musicals that I complain about anyway). Now that I've seen it, I'd say Cabaret fits perfectly within the decade, and, if we throw out auteur theory (which we should, because it's just silly), as representative of the New American Hollywood aesthetic and moral concerns as any work by Martin Scorsese or Francis Ford Coppola. Social consciousness, grimy sets and costumes, dark lighting, beautiful cinematography (an especially pleasant surprise, given that musicals tend to pride themselves on inventive but not particularly beautiful camerawork), complicated sexuality, a bleak, bleak ending—it's all here, and I liked the film a whole lot. In fact, Cabaret is now probably my favorite musical on this whole AFI list[2] so far behind The Wizard of Oz (and Nashville, if you count that). Cabaret succeeds in taking that position largely because it works as an anti-musical, in the same way that films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Godfather: Part II could be called, respectively, anti-sci-fi and anti-gangster movies, in that it majorly tweaks or ignores many of the genre's conventions. The biggest nose-thumbing Cabaret gives the musical genre is that it almost entirely forgoes the device of delivering plot and character through song, instead relegating almost all of its music to the actual cabaret stage, which makes the music feel totally organic and integrated into the more serious intonations of the plot, an effect almost entirely foreign to most conventional musicals (where, I realize, the heightened artificiality is a good portion of the fun). The disconnect from plot development gives the songs a chance to relate to the characters in a more tangential, thematic way that pays especially well when the editing cuts from the stage to the characters going about their lives. Oh, and just so I don't give the wrong impression, this movie, for all its '70s dourness, is still a lot of fun. The cabaret performances are giddy, hilarious, catchy, and the performances, especially Liza Minnelli[3], are impassioned and charismatic. This one's a winner.

Per usual, I'd love some discussion on these films. Until next time!

If it strikes your fancy, you can read the previous entry, #s 58-60, here.

Update: The next post, #s 61-63, is up here.

1] In fact, Sullivan's Travels didn't make it onto AFI's original 1998 list, being only added for the 10th anniversary version that I'm working through now.

2] The irony is not lost on me that, when one of my perennial complaints of movie musicals is that they rarely capture the energy of a live stage performance, one of my favorite musicals ended up being a movie whose music is very self-consciously confined to an actual stage. For what it's worth, though, I should probably admit that I've never seen the stage version of Cabaret, so who knows how I'll feel about this film once I do.

3] aka Lucille Austero! I'd like to think that her character ends up escaping to Southern California and, late in life, developing crippling vertigo and an unflagging infatuation with one Buster Bluth. We can only hope—it's certainly a happier ending than Cabaret suggests for her.

Another few days, another few AFI movies. Yeah, that's about all I've got for an intro. Move along.

61. Sullivan's Travels (1941, Preston Sturges)

I'll be honest here: it has been a very long time since I last saw Sullivan's Travels. Consequently, this discussion is going to have to be kind of vague on the details of this film. I cannot remember, for instance, if the cinematography or direction is any good (though given that it's Preston Sturges running the show, I'd guess they're both at least functional, if not exemplary), so those are topics I'm going to avoid. What I do remember, however, is the plot. And man, that plot is good. It's not just an engaging, funny, slightly satiric story (although it is all those things); it's a story that has such a potent thematic thrust regarding the filmmaking establishment that its barbs are still poking modern-day Hollywood. It's actually kind of hilarious that this film made it onto the AFI list at all [1], given that Sullivan's Travels is an indictment of the self-serious prestige machine that fuels the Academy Awards, film criticism, and, yes, the American Film Institute. When the film's fictional filmmaker John Sullivan decides that comedies are just as socially valuable as prestigious social dramas with capital T Themes, he might as well be directly addressing this list, which, I remind you, is made up of (not counting musicals) less than 10 percent comedy and about 80 percent prestigious social drama with capital T Themes. Now, I like prestigious films as much as the next guy (and goodness knows I've praised plenty of them on this blog), but there's something sort of rousing to Sullivan's Travels's critique. To quote another film on this list, "Make 'em laugh," dangit!

62. American Graffiti (1973, George Lucas)

In discussing George Lucas, a lot of people focus on Star Wars, which is entirely reasonable considering that the original Star Wars trilogy and especially Episode IV are some of the biggest, most groundbreaking, most culturally significant, most aesthetically successful movies of all time. But what often gets lost in all the galaxy-far-far-away shuffle is poor old American Graffiti, the little movie that immediately precedes Star Wars in Lucas's filmography. And that's kind of too bad because not only is American Graffiti, like Star Wars, a great, distinctively personal film (as well as proof that at one time, George Lucas was actually a good writer), it also is pretty groundbreaking in its own right. The extent to which it incorporates classic rock and soul tunes into its soundtrack was pretty much unheard of at the time of its release, and it remains one of the most technically and thematically sophisticated uses of pop music ever in American cinema. The wall-to-wall-songs approach to its soundtrack has also been hugely influential on subsequent generations of filmmakers—you can bet that Dazed and Confused and Do the Right Thing, to name two of American Graffiti's biggest heirs, would sound a lot different without it. And speaking of those heirs, another piece of American Graffiti's groundbreaking legacy is that it (to my knowledge) pretty much invented the whole cinematic subgenre of wistful coming-of-age stories that take place over a single night. Movies like Sixteen Candles, Superbad, and yes, Dazed and Confused all work within this mode and basically follow the structure of American Graffiti verbatim, with a series of mostly episodic (and mostly comedic) events slowly escalating to catharsis at dawn. It's a killer way to construct a plot, and it's always a treat to see a movie adopt the form. I've talked so much about the influence of American Graffiti that I've run out of room to praise the actual movie itself. Don't let my lack of discussion fool you; American Graffiti is great, and, for what it's worth, I think it's better than at least sixty-seven percent of the Star Wars films. I'm guessing it's pretty obvious which sixty-seven percent.

63. *Cabaret (1972, Bob Fosse)