Hello all! I'm working my way through AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies

list, giving thoughts, analyses, and generally scattered musings on each

one. For more details on the project, you can read the introductory

post here.

So, this post includes the second (and last) of the Stanley Kubrick movies on this list, and as with 2001, I'm less than thrilled with it, although I do like it better than that original film. Why oh why couldn't AFI actually pick the Kubrick films that I actually like? Anyway, all that is to say that I'm sorry for the overlong writeup of A Clockwork Orange. Hope the mostly reasonable length of the other two entries makes it okay.

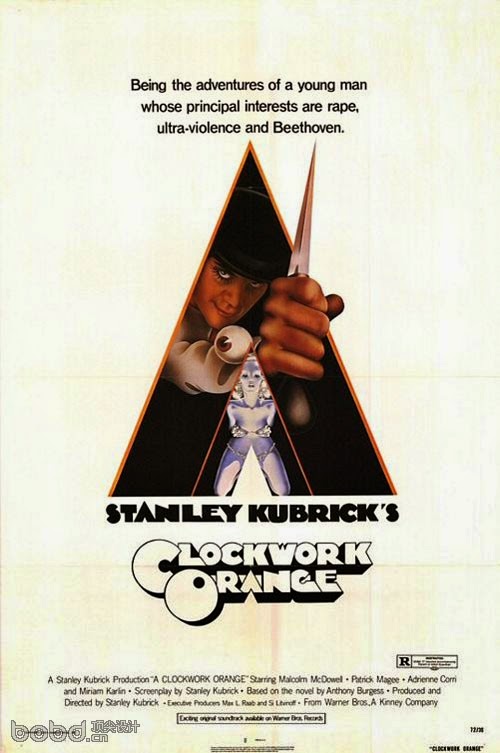

70. *A Clockwork Orange (1971, Stanley Kubrick)

This movie is such a mess that I'm struggling to find a good starting point for this discussion. It's not so much "bad" as poorly calculated, so I guess I might as well begin there, especially considering that Stanley Kubrick is one of the most calculating movie directors of all time. And that's not a bad thing! This being a Kubrick film, of course, A Clockwork Orange is a technical masterpiece, full of inventive camerawork, striking imagery, and some of the coolest frame compositions out there. The thing is, as I see it, that technical mastery is also what causes one of the film's biggest problems: it's intentionally filmed as a comedy [1], which of course begs the question of whether or not such a plot as this one (one, in case this work's reputation has eluded you, that is chock full of beatings, rape, torture, and grotequery) should be filmed as a comedy. That question gets into the whole issue of whether there are any subjects off-limits to humor, an issue I don't feel equipped to weigh in on, but I will say this: the jauntiness of the proceedings makes it terrifically difficult for me to figure out what to do with the film's violence. I have no doubt that Kubrick intends for this film to be against rape and gang violence, but it's also possible for there to be miles between authorial intent and actual effect. To be sure, Alex's leering gaze in the first shot makes it clear that our protagonist is as much villain as audience surrogate (though, troublingly, he's also that in the prison and rehabilitation sequences); that being said, there's also something undeniably seductive about the way the violence is situated from Alex's (often joking) perspective, a calculated choice that Kubrick has made to no doubt show the depravity of the character, but a calculation that also hinges so much of its impact on assumptions about the psyche of his viewers that I really think the power of those scenes has fumbled from the filmmakers' control. There's also the problem that many of Kubrick's choices in those scenes, even the more effective ones, often involve objectifying the (mostly female) victims [2]. I do recognize that this film is a satire and that this objectification often serves the satirical points of the film quite well (esp. in reflecting the effects of the hypersexualized society in which Alex lives), but objectification for a purpose is objectification nonetheless, and by gum, when you're dealing with victims of rape, I'm not sure if objectification should be on the table at all. I'm getting rambly, so let me close out by saying that I might be more charitable toward the unintended consequences of the satire if I had a feeling that the satire were serving a larger social point beyond pure nihilism, but I just don't think that's the case. The film, for all its unintended effects, does not want to be on Alex's side, but neither does it want to be on any other side or take any position at all, it seems, given the horrific (and often parodic) nature of the government's penal system. It's a movie that wants to be somehow against both criminal behavior and criminal rehabilitation. At its most constructive, it seems to say that individual autonomy is more important than morality [3], but even then, I'm hesitant to assign that interpretation for all the contradictions it makes in the movie as a whole. So again, it's not a bad movie (it's far too technically accomplished and smart for that), just one that seems horribly (dangerously?) messy to me.

71. Saving Private Ryan (1998, Steven Spielberg)

After the overlong response for A Clockwork Orange (sorrynotsorry, folks), I'll be brief here. The common critical narrative on Saving Private Ryan has become that it's a great movie in its opening Beaches of Normandy sequence and merely an okay movie for the other two hours of its duration. And, boringly, my opinion is basically just a variation on that idea. The first thirty minutes of the film are some of the most visceral, terrifying, and effectively anti-war war movie minutes ever put to film. It turns World War II (our "righteous" war, let's not forget) into the chaotic horror film that I feel most cinematic battle scenes should be. War is hell, goes the banality, and Saving Private Ryan's storming of the beaches is one of cinema's most hellish, with imagery right out of Dante's Inferno (or, you know, real life, which war movies are all too good at letting us forget). The rest of the movie, I have to agree with the critics, is pretty by-the-numbers, as far as war movies go, and it leans a little too hard on the stop-being-a-coward-and-be-a-man-and-kill-people ethic that rubs me wrong about some other war movies. That being said, I do think that in the final fifteen-or-so minutes, the film becomes near-great again, building to a powerful climax with the (spoilers) sacrifice of Tom Hanks's character [4]. So there's that. Yeah, overall, a movie I like with a few essential scenes, but so many other films in just Spielberg's filmography alone deserve this spot, so whatever.

72. The Shawshank Redemption (1994, Frank Darabont)

Well, what a nice surprise. I've spent a good deal of time poring over this AFI list, even before beginning this project (because, you know, I'm a horrible nerd for these sorts of things, which I realize is a bad habit and I should feel bad), but until preparing for this post, I had completely forgotten that The Shawshank Redemption was on this list. What's wonderful about that for me is that the movie is such a non-AFI movie, by which I mean that there is next to nothing Important about it. It's not the work of a so-called "auteur" like Kubrick or even that of generally well-regarded director like Spielberg; Darabont is, in fact, primarily known for directing inoffensive adaptations of Stephen King's work, which is about as glorious a populist legacy as I can envision. There's nothing particularly innovative about its cinematography, either. It's not a movie driven by Big Important Actors like Marlon Brando or Orson Welles playing self-important roles; the acting in Shawshank is top-notch, of course, but it's of the smaller, warmer variety that tends not to get lots of attention from the codifiers of Hollywood history. It's also not a movie with Big Social Themes; although it's set in a prison, the film (along with the Stephen King novella it's based on) has almost zero interest in saying anything socially relevant about the state of incarceration in the United States in the mid-20th century or in contemporary times or ever (compare that, for example, to A Clockwork Orange's hyper social awareness). No, more than anything, The Shawshank Redemption just wants to give its audience a fun, feel-good time. That's a mission statement sorely lacking from so many of the dramas on this list. Now, as I'm sure you can tell from some of the other posts in this project, I love me some self-important dramas, but the idea that films with weighty themes and historical significance are the only films worth honoring is so toxic to cinema culture that it's a genuine relief to me that something like The Shawshank Redemption (an antidote to that toxicity if there ever was one) has gathered enough critical inertia over the years and years of cable reruns to emerge on this list.

Agree with my takes on these movies? Disagree? I'd in particular love to hear someone call me out on my ideas about A Clockwork Orange, as I'm still very conflicted about the film. Or you could call me out on what I have to say about these other movies, too. It's all good.

Until next time!

If you want, you can go back and read the previous post, #s 67-69, here.

Update: The next post, #s 73-75, is right here.

1] There are a lot of indications that A Clockwork Orange is a formally comedic work, but the two main elements that I would cite are the abundance of wide-angle distortions (a technique often used to frame silliness) and the carnivalesque direction of the acting, both of which exaggerate the onscreen images to a somewhat humorous effect.

2] The first rape (the one Alex and his droods walk in on at the beginning) is a good example of what I'm talking about. The film is definitely indicting Alex's callous attitude toward the woman, but it's also a scene in which the depiction of the violence is bloodless enough to sort of emphasize the nakedness of the woman more than the violence itself, which again is keeping with Alex's perspective, but that's a mighty irresponsible stance for a film to take, even for the purpose of satire.

3] Which, again, I think is sort of an irresponsible and sloppy message to ground satire in, especially when the film adaptation lacks the (admittedly clumsy) final chapter of the original novel, in which Alex discovers that the purpose of that autonomy is to develop a moral awareness.

4] You know what bugs the heck out of me, though? That the death of Tom Hanks's character totally messes of the POV of the movie! Like, the whole film leads you on to believe that it's an elderly Tom Hanks in the graveyard at the beginning remembering all this stuff, and as a result, the whole movie is set in Hanks's perspective—only then it turns out that this isn't Hanks's memory at all because he's dead, so how on earth did we just remember everything from his POV?? It drives me nuts.

No comments:

Post a Comment