Movies

Palm Springs (2020)

It's really interesting to see a genre emerge, as one certainly has around these "time loop" stories, from a single work, i.e. Groundhog Day. I can't think of another example of that except maybe the Christmas Carol-type story? Anyway, I feel like the trajectory with this genre has been a slow move away from recreating the beats of Groundhog Day (a meticulously documented setup of the repeated day, followed by a long period of time wherein we see the protagonist question their sanity/deny the looped reality, only to eventually accept it and go on a ridiculous, nihilistic/hedonistic spree, etc.—y'all know the drill) to an understanding that the beats of Groundhog Day are familiar enough to the audience that they can be gestured toward with shorthand or even transformed/done away with completely. For me, the tipping point seemed to be Netflix's Russian Doll show, which did some really fascinating work digressing from the familiar thematic ambitions and outcomes of the genre, but now Palm Springs confirms retroactively that there was a tipping point to begin with, since it is build with the abstract tropes of the Groundhog Day premise not as something to be explained to an unsuspecting audience but as a set of assumptions to be recognized by and subverted for a savvy audience. I'm not going to say that this is the most experimental film of all time or anything (the visuals are pedestrian to a fault, e.g.), but there is something revolutionary within the specific context of this genre to have a time loop story in which two people (three, actually, but that's kind of its own thing) cycle through the loop. The complete isolation of Groundhog Day's existential fable becomes a story that's no less existential (the idea of creating meaning in an absurd universe remains at the forefront of this movie's mind, often explicitly in dialogue) but also ends up being far less isolated on a metaphysical level and ultimately a lot more human. For as much as I love Groundhog Day (and I do looove Groundhog Day) and its children, these sorts of stories often struggle to make the secondary characters who aren't stuck in the loop anything more than just NPCs in the protagonist's personal journey of enlightenment. By having multiple characters go through the loop, the story forces itself to reckon more fully with the significance of people's experiences outside of a single person's point-of-view, and in a way, the whole movie then becomes about not just creating a meaningful existence out of life's absurdity but also in recognizing and interacting with the meaningful existences that other humans around you have built. There's a reductive take on this movie that basically just boils down to "Groundhog Day, but a rom-com," but the actual effect of this movie is way more complex than that. It's not just a genre slapped on top of another genre (as much fun as Happy Death Day is, it's never really more than just "Groundhog Day, but a slasher"); it's a movie that makes genres interact with each other in productive and even profound ways. I find it really exciting that movies in this mold can be more than just "Groundhog Day, but..." It's weird to say that I responded to this as strongly as I did Bona-Fide Cinephile Classic(TM) Pickpocket, but there's a specific energy to this movie that has a strong resonant frequency with the way that since March I've basically been living the same day over and over again with my wife in our house and trying to figure out what that means. It's also weird that I apparently relate to media on COVID terms and feel okay ending this review with a "movie for our unsettled times" observation. I dunno, what can I say, I yam what I yam. Oh, and P.S., the mid-credits scene was super confusing to me, full disclosure. Grade: A-

Kes (1969)

I see this all the time with children, including the students I teach: these wonderful creatures whose abilities, interests, and/or life circumstances are ill-suited to the industrialized (or increasingly post-industrialized) world that they must inhabit as they grow older, and the process of inhabiting this world is also the process by which the things they find joy in are stamped out of their lives; this is obviously more acutely compounded if your only future is in a coal mine, as is our protagonist's here. I know the "loss of innocence" is a tale as old as time or whatever, but there's something specifically cruel about the way innocence is crushed in a mechanized world in which human life is only a component part of the machine that feeds production. Completely heartbreaking. Grade: A-

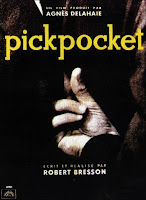

Feels a lot like Dostoevsky, which is not a criticism at all; the intersection of Crime and Punishment and Notes from Underground is a place cinema has fruitfully occupied for a long time (not the least of which by one Paul Schrader, who is apparently obsessed with this film), and it's cool to see its origins (or something close to it—I'm sure there's some other precedent that I'm missing). I'll have to think more about this movie beyond that, though. It feels vaguely unsettling, with a final scene that feels a little like Crime and Punishment's controversially redemptive conclusion or Taxi Driver's "happy" ending, both of which are still things I'm trying to work out in my head. But still, this is Good Cinema, a lot more immediate than the other Bresson I've seen (though I definitely prefer more overtly Christian Au hasard Balthazar), and it's a movie I'll probably return to sooner rather than later. Grade: A-

The Stranger (1946)

A pot-boiling Hitchcock knock-off directed stylishly by Orson Welles (such a shadowy movie). It's notable how anti-Nazi this movie is, almost as much so as the propaganda pieces like Lifeboat that Hitchcock directed during the war. It's a little inconsistent in interrogating Nazi ideology—one minute, you have scathing indictments like documentary footage of the Holocaust or a scene in which the Nazi says that Karl Marx doesn't count as a German because he was a Jew (darkly hilarious that this is what outs him as a Nazi to the U.S. government official, considering that the United States would be saying similar things about communists within ten years during the Red Scare), but then the next minute, the movie will lean into generic Movie Evil like how Nazis are bad because they will murder their wives with their bare hands. The clocktower climax is magnificent, though (is there a clocktower climax that isn't? Maybe the most reliable setting in film history), and generally, Welles's direction is strong enough to give some urgency to even the less engaging moments. Grade: B

No comments:

Post a Comment