You can read the post on The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe here.

You can read the post on Prince Caspian here.

You can read the post on The Voyage of the Dawn Treader here.

You can read the post on The Silver Chair here.

You can read the post on The Horse and His Boy here.

Let's not beat around the bush here: The Magician's Nephew, the sixth book published in The Chronicles of Narnia, is almost without a doubt, the most perfectly realized book of the entire series. Now, whether or not "most perfect" means "greatest" is a matter I have not quite sorted out yet[1], but what I do know is that it is the only Narnia book that comes within spitting distance of my perennial favorite, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Furthermore, unless I'm grossly misremembering The Last Battle, Magician also makes up the last entry of what we might call a sort of "hot streak" or even "trilogy of greatness" in The Chronicles, with the first two books being the aforementioned Dawn Treader and The Silver Chair. C. S. Lewis was on fire when he wrote these three books back-to-back[2], and as far as I'm concerned, this unofficial trilogy is the primary justification for Narnia's continued legacy in the pantheon of children's lit greats.

So just to clear up any confusion, The Magician's Nephew is definitely great. But I also called it "perfectly realized," and what I mean by that is this: while most of this re-reading project has led me to discover just how bizarre and flawed (albeit powerful) most of the Narnia books are, The Magician's Nephew is a novel that manages to distill the greatness from the series without accumulating the lopsided structure, incomplete character arcs, or any of the rest of chaff that I've mentioned in my reviews thus far. I called The Silver Chair a great novel, and it is, but I think even more than that book, The Magician's Nephew takes the fantasy of Narnia and works it into what most of us would recognize as a finely calibrated story.

And the key to that calibration is our protagonist, Digory Kirk.

Let's summarize for a moment. The Magician's Nephew takes place in London in the early 20th century[3]. A girl named Polly Plummer lives in a row of townhouses, and one day, she's out in her garden when she meets her neighbor, a boy named Digory Kirk who used to live in the country but now resides in London with his aunt, his crazy Uncle Andrew, and his deathly ill mother. The two strike up a friendship centered around the mutual discovery of a crawl space that runs along the entire row of houses where they can have secret meetings. They decide to use the crawl space to break into an abandoned house in the row, but they miscalculate the distance and end up in Uncle Andrew's study instead. It turns out that Uncle Andrew imagines himself a magician and has come into possession of some magic rings. The unpleasant man tricks the children in to touching the rings, which he says will transport them to another world. They find themselves in a wood filled with pools of water. The children realize that these pools represent different universes that they can enter using the rings, and they decide to try out one of the other pools before returning to their own puddle. They find themselves in a ruined civilization called Charn. Digory accidentally awakens an evil queen named Jadis, and against their will, she returns with them to Uncle Andrew's study. The queen promptly wreaks havoc in the London streets, and in a panic, Digory and Polly use their rings to take her (and, without meaning to, Uncle Andrew, a cab driver, and his horse) back to the wood and into the first world they can get to. This world is dark and formless until a lion (Aslan, of course) appears, creates life and landscape before their very eyes, and christens it "Narnia." At the sight of the lion, Jadis runs away into the countryside, and Aslan tells Digory that since he has brought this evil into the new world, he must also protect it by going on a journey to a garden to get the seed of a magic tree that will ward off evil. When Digory finds this garden with the help of Polly, Jadis is already there. She tells him that the fruit of the tree is a life-giving fruit that will cure his mother's illness, but Digory, though terribly conflicted, follows Aslan's instructions and returns the fruit to him. Aslan plants the tree, and when it has grown (which, in the magical new soil of Narnia takes a matter of minutes), he gives Digory fruit from the new tree. When Digory and Polly and Uncle Andrew return to their own world, Digory gives his mother the fruit, and she undergoes a miraculous recovery. The end.

Digory and Polly

So yes, The Magician's Nephew is a prequel to the entire series (even more so than I've described—for example, Digory grows up to be Professor Kirk from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe), but besides that, hopefully something you picked up on from that plot summary is that at the book's beginning, Digory has a tremendously sad life: he has lost his childhood home, his former life, and his friends, and most importantly, he's on the brink of losing his mother, too. In most books, this would not be particularly notable; think Huckleberry Finn, Oliver Twist, or even relatively lightweight fare like The Boxcar Children: literature thrives on the sadness of its protagonists. In most conventional storytelling paradigms, plot and character development stem from conflict, and almost always, that conflict grows out of a tragedy of some sort.

But for an entry in The Chronicles of Narnia, beginning with that kind of tragedy is a big deal, because up to this point, sadness and grief have not been central to the Narnia ethos. In fact, The Magician's Nephew is an anomaly in how desperate and broken it makes Digory's life in the outset. Think about the rest of the books: there's a hint of tragedy in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in the tossed-off reference to the Pevensies' flight from the bombings[4]; a twinge of sadness as the Pevensies await adulthood at the train station in Prince Caspian; some bullying woes for Pole at the beginning of The Silver Chair. But these are all minor occurrences, both in the books' treatment of them (these troubles are usually swept aside for more interesting, magical things in a page or two) and in their weight to the characters (none of them seem deeply distraught, and besides, none of their problems even approach the horror of the death of a parent). The only protagonist who even approaches beings able to lay claim to the same depths of grief as Digory is Shasta from The Horse and His Boy, but even then, Shasta's prospects improve drastically a few pages into the book, once he encounters the magic of Bree, the talking horse. Anyway, even if Shasta regards Arsheesh's cruel treatment with the same level of grief as Digory does his mother's illness, he doesn't show it.

By contrast, the first thing we see of Digory is his tear-stained face after he's been crying alone in his family's yard, and only a page and a half later, he's choking back tears again. What's more, the cause of this sadness isn't something that fades away after the introductory pages; Digory's mother is ill until the very last chapter, and we see tears come to his eyes at the thought of his mother several times on the way there. Digory's sorrow is deep and sustained in a way unlike anything any other character encounters in the series. Lewis's protagonists, when they aren't glorious little snots in the mold of Eustace or early Edmund, tend to be of the stiff-upper-lip variety, the kind of folks that call things a "bother" and face troubles with a clever, problem-solving resoluteness that protects them from any heartache too profound. They tend to be capable of joy but not grief—even Susan and Lucy, weeping at Aslan's corpse in Wardrobe, seem to be doing so innocently, almost like Pole crying about the bullies, the way people cry at momentary cruelties or a scrape on the knee. Digory is in for the long haul, and he realizes it. His story is sad and affecting, all the more so because the book gives weight to the fact that Digory knows that once death takes your mother, you never get her back. He's a boy that Lewis renders with tenderness and compassion, and as a result, Digory becomes the series's most bleedingly human character.

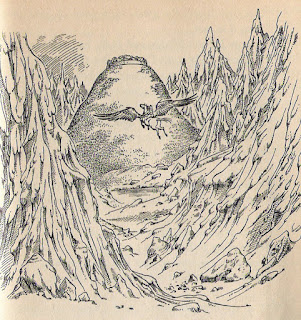

I include this picture here for the sole reason

that I think it's one of the series's best.

This accomplishes two things. First, on a purely technical level, it gives the book a dramatic drive that even the more propulsive books in the series can't match. I mean, with Digory's grief, The Magician's Nephew has a sustained dramatic conflict affecting a character for the entirety of the book; that's astonishingly rare in The Chronicles of Narnia. But even the books with a similar single conflict don't quite match Magician's heights. The Silver Chair may be a tightly plotted novel with an exciting hook—who doesn't love a missing person plot?—but for all its twists, even I have to admit that it's central premise is a little dry on the emotional front (unless we identify with the largely absent King Caspian, something the book does not encourage us to do). The Magician's Nephew, on the other hand, outdoes it by girding its exciting, world-jumping plot with emotional stakes unparalleled in even that masterful novel: Digory is grieving his mother's imminent passing. Plots with exciting twists are one thing, but plots with exciting twists and emotional stakes are even better. This novel is the series's most effective page turner because it's the book most engineered to make us care about what's happening. Take, for example, the book's climax, where Digory must choose between saving his mother's life by stealing the magic apple for himself or following Aslan's commands by returning it to the lion to protect Narnia. Throughout the Narnia books, we see characters face similar conundrums, where they must either act selfishly or obey Aslan, and honestly, it's never all that interesting because it's always obvious which choice is the right one: of course they should follow Aslan and not side with the White Witch, etc. And honestly, the right decision is pretty obvious here, too—Digory knows he should obey Aslan. However, the cost of obeying Aslan is never as steep as it appears here, and because of that, Digory's choice is one of the most compelling moral actions in the series. Unlike the rest of the "do the right thing" scenarios, there is real weight to the ostensibly wrong choice. And that's all couched in Lewis's depiction of Digory as a character whose world is profoundly broken.

Second, the grieving, compassionate humanity with which Lewis renders Digory forms the thematic core of everything this book does. The Magician's Nephew is a novel about dealing with grief—specificially, Digory's. And I do mean dealing with grief. I don't think it's any accident that Lewis waits until more than half the novel has passed before introducing even a sliver of hope for Mrs. Kirk's recovery[5]. By not giving us the narrative logic necessary to see Digory's mom's recovery as a possibility, Lewis makes us focus not on how Digory saves his mother but on how Digory lives with the fact that he can't do anything for his mother—to put it another, broader way, how Digory manages to cope with a world full of evil and tragedy; how Digory finds beauty in a world he calls "a beastly hole." And that focus leads to some rather profound insights into the series's pet motifs of storytelling and fairy tales (you knew that was going to come up sooner or later, didn't you?).

It might help to look at the novel's opening chapter just a little more in-depthly. I've already mentioned that the novel opens with Polly finding Digory crying, which is, of course, heartbreaking. Besides introducing Digory, though, what's interesting about that scene is what ultimately diverts the story away from just focusing on Digory's grief. Lewis's narrator writes that "to turn Digory's mind to cheerful subjects," Polly asks him if his Uncle Andrew "is really mad." Which, at first blush, seems like one of the absolute worst questions you could ask someone who was already feeling bad about their family problems—"I'm awfully sorry to hear about your dying mother; now why don't you tell me about your insane uncle?" But that question makes a lot more sense once you see where it leads. Once Polly and Digory begin to talk about Uncle Andrew, it becomes clear that they aren't talking about him because he's a crazy uncle; they're talking about him because with him lies the promise of discovering a fantastic story. Uncle Andrew is a mystery, not one of those ugly, unpleasant, real-life mysteries like "When will Digory's mother die?", but a romantic, storybook mystery—he might be a coiner or have a crazy wife shut up in his room, to name two possibilities the children name. "Or," Digory adds eventually, making the storybook connection even clearer, "he might have been a pirate, like the man at the beginning of Treasure Island." This is how Digory finds beauty in life and how he deals with grief: through stories. More specifically, through fantasy[6] stories.

That attraction to storytelling as a means of dealing with grief is there from the book's outset, and it only becomes more apparent as the book progresses and fantasy becomes more and more a part of not just the children's imaginations but the novel's reality. With Uncle Andrew's magic rings and the trip to the Wood Between the Worlds, all the storytelling possibilities Digory and Polly have thrown around become actualities. They can jump from world to world, story to story. They literally immerse themselves in fantasy by jumping into the pools in the wood, and they can bring back into their own world the things they have learned and acquired. Of all the Narnia books, The Magician's Nephew is the one that spends the most time in our world, and it's the only one besides Wardrobe where major plot points happen on Earth, outside of Narnia. This is important. Most of the Narnia books are interested in fairy tales and storytelling in one way or another, but The Magician's Nephew is unique in that it's interested in how fantasy interacts with reality. Nowhere else in the series is the division between "fantasy/Narnia" and "real life/England" more permeable. Let's not forget that the first page of the book also tells us that "in those days Mr. Sherlock Holmes was still living in Baker Street." This is a book in which the fantasies we read about in literature—be they the wicked Queen Jadis[7] or Atlantis or magic rings or cure-all apples—have a life in an other, fantasy realm and in "real-life" London. In The Magician's Nephew, C. S. Lewis argues that these fantasies are vital sources of beauty and hope for us as we live through our own world.

I don't think this is any sort of prosaic statement on Lewis's part. A lot of this "beauty" and "hope" takes the form of less savory things like witches and ruined civilizations, and even the initial storybook mysteries that Digory and Polly suggest at the book's beginning aren't exactly pleasant ones: counterfeiters, pirates, insanity. It's not that Lewis thinks that we should disappear into fantasy in order to buffer ourselves from the pains of the real world. Digory could stay in Narnia or Charn or the Wood Between the Worlds and forget about his mother, but he always returns to his home in London. What I do think Lewis is trying to show is that stories are how we are taught to see truth, and by knowing the truth (be it God Himself, whom Lewis found through his own studies of literature, or just a deeper understanding of the complexities of life[8]), we can better interact with our own world and deal with pain and hurt and brokenness in a more mature way.

Of course, it's true that The Magician's Nephew does end up kind of rectifying every one of Digory's woes through magic, and I suppose this could be considered Lewis's argument for (or maybe even fallacy of) escapism. I'll admit that Lewis lays on the happy ending a little thick, even for the Narnia books: not only does Digory's mother get better but also some random relative dies and bequeaths Digory's family his immense fortune, which allows his father to retire from his job in India and the family to move together to a beautiful country estate. However, I have two things to say about that. Firstly, any ending that allows for the scene in which Digory feeds his mother the apple is a-okay in my book, as that scene is one of the most poignant, tender passages Lewis ever wrote. Secondly, I'd also say that Lewis is totally aware of the escapism of that ending, which is why he drives the prequelness of the book so hard in the end. The final pages of the novel are chock full of allusions to The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe—Digory builds the wardrobe, the country estate is the same one the Pevensies live at during the war, the lamp-post in Narnia turns into Lantern Waste—and at least one of the effects of all of these allusions (in addition to the satisfying feeling of watching everything click into place from the other books) is that it calls attention to the fact that The Magician's Nephew is a book itself and not real life and that although Digory got to live his fantasies thanks to the rings, our interactions with the stories in books must be more metaphorical. No, there are no magic silver apples that we can bring from other universes to heal our mothers[9]. But that doesn't mean that there isn't value in talking about a fantasy world in which there are.

This book, y'all.

And... gaaaahh, there's so, so much that I still haven't said about this book! The Magician's Nephew is so rich that I've spent this entire post babbling on about Digory and spent next to no time talking about Uncle Andrew (who ranks with Eustace as one of the great heels of Lewis's creation) or Jadis or the knowledge/power thematic connections or the urban/rural divide or Polly (who isn't as interesting as Digory or Pole but still does alright as a pricklier version of Lucy) or even just the wonderful, wonderful imagination and imagery on display in this novel—seriously, Charn is one of the most haunting, evocative things Lewis put on the page, and the same goes for its eventual fate as a small hollow in the Wood once its puddle has dried. But a post has to end somewhere, and I guess I have to end it here.

But that doesn't mean you readers have to stop! I know I've focused rather narrowly in this post, so let me know what I missed about the novel. I could talk for pages and pages about it, and I'm sure at least a few of you out there share my enthusiasm. Feel free to share in the comments or let me know otherwise about your own thoughts, feelings, likes, dislikes, etc.[10]

Until next time (and the conclusion of the series!)!

1] Dawn Treader, a book much too messy to ever be called "perfect," has an odd, powerful greatness that makes the shagginess of its form a non-issue.

2] The Horse and His Boy, though published between The Silver Chair and The Magician's Nephew, was actually written earlier (hence the references to it in The Silver Chair).

3] To be completely accurate, the narrator says that the story happens "when your grandfather was a child." My grandfather was a child in the 1940s, but if you imagine the "your" being some idealized young reader picking up this book in 1955 (when this book was published and my grandfather wasn't even twenty), we can imagine that it's supposed to be about fifty years prior.

4] Something the 2005 film ran with, to great success (the added emotional weight was definitely one of the film's strengths).

5] And even then, it's the very slimmest of slivers, hinging on a figure of speech about his mother being cured by fruit from "the land of youth."

6] I mean, really. What else would you call Treasure Island? I know there's no magic, but as far as the snooty world of literary studies goes, this level of genre fiction basically resides all in one big clump. Lewis, an academic himself (though far from a snooty one) is aware of that, I'm sure.

7] Whom Wikipedia tells me is basically an Edith Nesbit character come to life in Lewis's world from her novel The Story of the Amulet.

8] As, I think, Uncle Andrew learns from his encounter with that "dem fine woman" Jadis.

9] At least, I don't think there are. If you have evidence to the contrary, let me know pronto.

10] One final note that I didn't quite know where to put in the post: it's almost certain that The Magician's Nephew is the most autobiographical of the Narnia books. Not only is it set during Lewis's own childhood (and colored by quite a bit of nostalgia, as in the opening where he says "the meals were nicer" back then), but Lewis's own mother was also taken ill when Lewis was about Digory's age. Sadly, just a few months before his tenth birthday, C. S. Lewis's mother died, which adds an extra layer of poignancy to Digory's situation and the novel's ending. This is the ending Lewis never got.

I'm so sad you didn't talk about Jadis and Charn at all! Charn captured my imagination as a child to an immense degree. Such a fascinating idea! Jadis' description of the final war is so horrible, tragic, and compelling. I found Jadis to be a much more interesting character than the White Witch, who is more of a general specter of evil. Jadis, as queen and heir of this ancient line of immensely powerful rulers, is overwhelmingly proud of her lineage. You almost feel bad for her, in a way. She's vicious and cruel, but Charn was not a happy place before she arrived either.

ReplyDeleteThat said, there is quite a bit of similarity to the issues with Calormen in the depiction of Charn. It's very distinctively a fantasy of an "eastern" city as imagined by the colonial British mind fed on 1001 Arabian Nights and Oxford histories of Babylon, with its flying carpets and temple drums and human sacrifices. I'm pretty sure there's a reference to the royal line of Charn having genie blood as well? So while Charn is an impressive and ancient place, it's also got that kind of condescending European perspective on its glory. Charn's descriptions as "cruel," proud," and "decadent" are in part linked to its "oriental' status. Diggory (a white English schoolboy of the early 20th century) is the one who chooses Narnia's path forward, away from the "cruel empire" model of Jadis and Charn. It's all a bit imperialist, really. Especially with the whole "humans have to be kings of the beasts" idea Aslan pushes on Narnia.

I'm really bummed I didn't get to Charn and Jadis, too! I was similarly fascinated with the place. The Witch's monologue about her war with her sister and how she used the Deplorable Word is just chilling and kind of metal. That hall of "waxworks" is a great storytelling shorthand that Lewis came up with, too--it shows the decay of Charn's leadership that probably mirrored the decay of the land itself. We get a sense of the history of the land without being told outright. And speaking of the Deplorable Word: it's got to be a nuclear weapon analogy, right? Especially with Aslan saying to Digory that someday, people on Earth will discover a secret just as destructive. Either way, I'd say it fits in neatly with a sub-theme of the novel about knowledge, where people "dig too deep" into the secrets of the world in the name of science or learning--see also: Uncle Andrew's meddling with magic beyond his understanding. I know Lewis wasn't exactly anti-science, but he also definitely was not a fan of science divorced from morality, which is what I'm sure he saw a lot of the advancements of the nuclear age as being.

DeleteAs far as the racial/cultural elements to Charn, yeah, they're there, though I'd say that they aren't nearly as troublesome as with Calormen. There's definitely a Babylonian/Persian/Iranian vibe to the Charn imagery, especially the illustrations (there's one of a crumbling fountain that definitely looks like the Lion of Babylon), and you're right about the associations with Jadis's character. Two things make this better than Calormen, though: 1) Jadis is clearly white/European, even if culturally, she's much more Asian, so at least her character doesn't have the racial component that makes so many of the Calormene characters so uncomfortable to read about; and 2) Charn feels more Babylonian than anything analogous to modern-day Iran or Middle-Eastern cultures, something that isn't true of Calormen. With the emphasis on ancient civilizations, I think some of the colonial, condescending perspective is mitigated, if only because the land seems to be more of an appeal to myth and legend than any contemporary stereotypes. But yeah, I can still see how there could be problems with the Charn depiction.