At this point, nothing more than the musings of a restless English teacher on the pop culture he experiences.

Monday, December 22, 2014

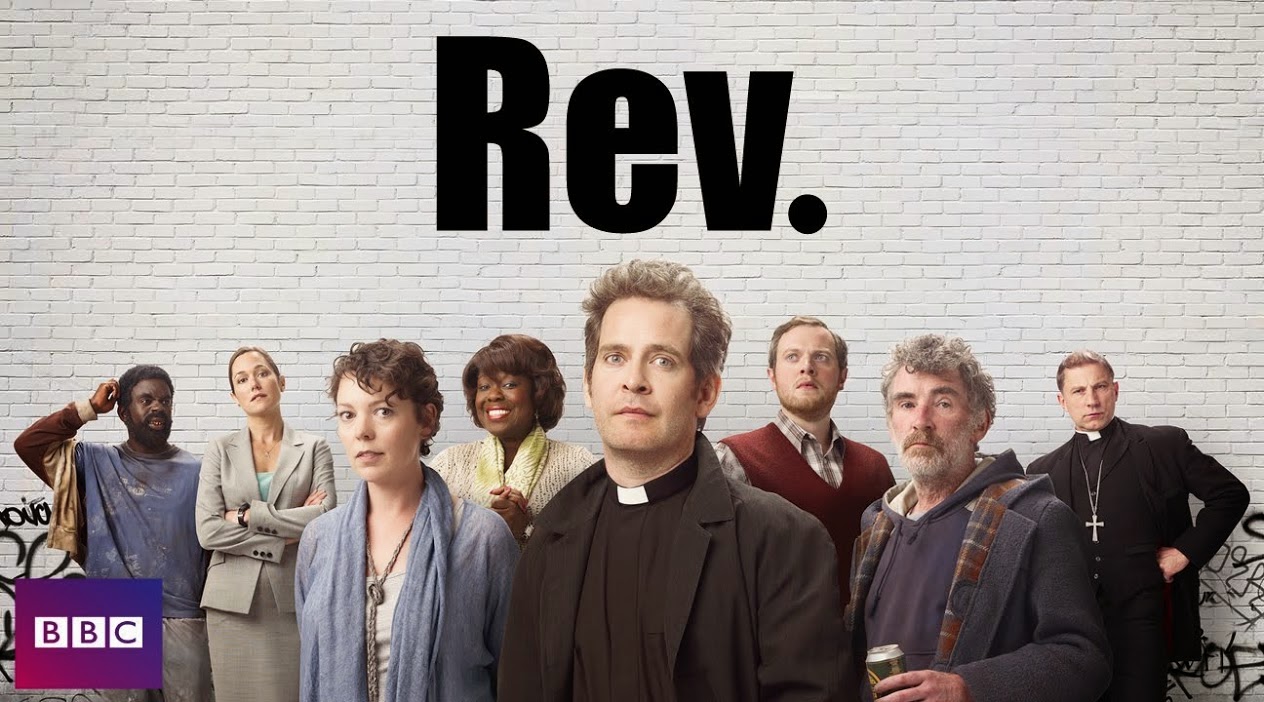

Rev., Christianity, and the Best TV of 2014

This time of year, you hear a lot about the best of the past twelve months' culture—the best movies, books, new species (?), etc. I've even gotten into the fray myself with my previous post on my favorite music of the year. 'Tis the season for list-making, after all.

Because I'm a helpless dork for that kind of arbitrary coding of pop culture, I've been reading a lot of these lists. In particular, I've been interested in seeing what the various culture makers are putting on their Best TV of 2014 lists. And as good and interesting as the selections on those lists have been[1], I've noticed that one of my favorite shows of the year has been absent from most of them, so I just wanted to take a moment to give it some much-deserved praise on this blog. That show is Rev.

Rev. is a British show that aired its third (and probably final) series this past summer. It's about Adam Smallbone, an Anglican vicar (Tom Hollander, who also co-created the series) who is put in charge of a small inner-city London church after spending several years in a rural parish. That's a premise that might as well be the setup for a typical fish-out-of-water sitcom, and nominally, Rev. is a sitcom, with its half-hour format, goofily framed secondary characters (of which my favorite is Archdeacon Robert [Simon McBurney], Adam's wry and antagonistic supervisor), and comedy-of-errors plots. The show is often very funny, especially in its first series, where it leans most heavily on its sitcom proclivities.

It's also a show that, for all its humor, has considerable dramatic gravitas, which is part of the series' greatness—we have plenty of funny sitcoms, British and otherwise, but the list of those that are also interested in serious dramatic stakes for their characters is much shorter. St. Saviour in the Marshes (the London church Adam works at, and yes, I'm jealous I don't go to a church with that name) is a parish struggling to maintain attendance and financial stability, problems that affect in serious ways not just Adam and his wife but also the few steady church members, many of whom (being in the inner city) live in poverty and homelessness. Though its examination of these problems are often told through jokes, the show treats them and the characters with dignity and compassion. There's a real sorrow for a broken world at the heart of the series.

But even more than that sorrow, what I think makes Rev. truly great is its handling of the Christianity at the center of its characters' lives. When most contemporary Western pop culture deals with Christianity (or really, any religion, but, being Western, it's most often Christianity that's dealt with), it does one of two things that I consider problematic.

The first is that it starts from the premise that belief in the religious supernatural is inherently foolish and/or destructive. See: the works of Woody Allen, for example (though much of that deals with Judaism), Stephen King, and mid-though-late-career Ingmar Bergman. Works that start with this premise are often excellent at analyzing the types of crises that can lead people away from faith or can cause organized religions to hurt people, but they often stumble in depicting with compassion and nuance sincerely faithful individuals[2]. When your story grows from a belief that a religious reality is false, it's difficult to have insight into religious belief without condescending from that premise.

On the other hand, there's also the second problem that pop culture tends to run into, which is that it assumes that the existence of the religious supernatural (and often a very particular brand of religious supernatural, too[3]) is self-evident. Admittedly, this problem is almost exclusively the property of the Evangelical stable with the likes of Courageous, Facing the Giants, and God's Not Dead, but it's the loudest counterpoint to the first problem and therefore worth discussing. Only cynical blindmen and villains can possibly doubt the existence of God/the power of prayer/the holiness of the Church once the right theology has been explained thoroughly enough, these works often say[4]. As a result, Christianity tends to be seen through rose-colored glasses, with the redemptive elements of faith and church community emphasized (often to the point of accidental self-parody) and the possibility that living according to religious beliefs can sometimes be a really, really hard thing to do downplayed. With these artistic endeavors, it's difficult to have insights into religious belief because that belief is assumed to be stable from the start.

Rev. belongs to an exceedingly rare class of art that not only avoids those two issues but also presents a meaningful and compassionate view of humanity through its depiction of Christianity. Its characters are devoutly religious people who pray, believe in miracles, and serve in church, and the show's depiction of that is neither condescending (there is never the suggestion, for example, that it's anything less than intelligent for Adam to pray to God when he needs guidance) nor self-satisfied in that faithfulness. Adam wrestles with doubts about the nature of his faith, God, and his church duties, but that wrestling is shown as a natural part of his existence, not a catastrophe (as it surely would have been in Evangelical art) or a step toward secular enlightenment. Neither is Adam (or any other character) perfect; he bumbles and makes mistakes, sometimes grave ones. He's a human being, after all, and his existence is peppered with the same moral struggles (deception, infidelity, anger, selfishness) that all humans encounter. The Church of England, being made of humans, isn't perfect either here. It's corrupt, it's petty, it's greedy, it's complicated by bureaucracy, but it's also never dismissed outright. Adam's parishioners gather, worship, experience joy and beauty and hope through the mechanism of that Church, and that's something the series never forgets.

Beautifully, Rev. posits that even though the Church is imperfect, it is worth caring for. Much the same goes for the show's view of the human race. I said above that it was more the treatment of Christianity than the sorrow for brokenness that makes Rev. great, but perhaps what I should have said is that its greatness lies in the way its sorrow for brokenness informs its depiction of Christianity. More than almost any piece of pop art I can think of, Rev. recognizes that the problems in organized religion are rooted in the same problems that inform human nature. The show's view of Christianity is something that grows out of its larger humanist spirit, the one that sees worth in showing compassion to even the lowest characters. The characters and their church aren't all good, but there's something at their core that absolutely is. Deep inside the human experience, whether it's the experience of day-to-day life or of Sunday worship, is something that can be redeemed.

And that's why it's my favorite TV show of 2014[5]. I totally recommend seeking it out if you get a chance; as of the writing of this post, all three series are streaming for free on Hulu, so there's really no excuse, right?

Until next time.

1] We're at an interesting point in television history where, following the endings of several elder statesmen of TV's "Golden Age" (Breaking Bad and 30 Rock, to name two, not to mention the impending end of Mad Men in the next few months), there's no longer as much monolithic critical consensus surrounding "elite" shows as there used to be during the high-classical era of Tony Soprano and HBO's mid-2000s output. Television is more fractured than ever, and that means there's equal room for everything from Over the Garden Wall to Louie.

2] This is less true of Ingmar Bergman's films, which are nothing if not nuanced and compassionate toward every single human being ever. But I don't think there's any doubt that his later films are also very much within a post-Christian mindset which restricts its depiction of faith to misery and wishful thinking.

3] Hint: it rarely includes transubstantiation.

4] I'm exaggerating a bit for effect, but the core idea is there.

5] Tied with Mad Men, Louie, and Over the Garden Wall, that is, but hey, those are already getting plenty of love elsewhere.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment