Ahhh, Winter Break.

Movies

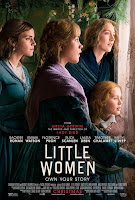

Little Women (2019)

There are minor spoilers in this review, so I guess if you don't want to be spoiled on the plot of one of the most widely known stories in American literature, beware.

To call this "Greta Gerwig's" Little Women undersells, as auteur theory always does, the tremendous collaborative authorship among the writer/director Gerwig, the composer Alexandre Desplat, the cinematographer Yorick Le Seaux, and what is undoubtedly one of the most perfectly assembled casts of the past decade—all of whom take their various roles and inhabit them to such a deeply magnificent extent that they feel like individual works of art of their own authorship. And yet the most impressive and marvelous feat about this particular adaptation of Alcott's oft-adapted novel seems directly attributable to Gerwig herself, and that is the way the movie positions itself in relationship to its source text. This movie is cinematic literary adaptation executed to perfection; Gerwig has scripted the film with a clear and earnest love for Alcott's work, but crucially, more than any other Little Women adaptation I've seen, she also understands this story deeply enough that she's not too precious with it to tweak and tighten in order to make it the best version of itself, underlining buried subtext, inventing incidents to fill in gaps, drawing connections between seemingly unrelated character beats, shuffling the structure to draw out the poignancy of its arcs, all while feeling 150% within the spirit of what Little Women has meant to its millions of fans for the past 150 years. It's Gerwig's structure in particular that's such a remarkable act of creation; rather than tell the novel's story chronologically, she's taken its two volumes and cross-cut between them, jumping back and forth between the March women's adulthood and idyllically remembered childhood. It's a seemingly simple creative decision, but the story flourishes around it. Little Women has always been a story about siblings, but with its cross-cut structure in this movie, it becomes—and whether this is in the book and lost in other adaptations or simply Gerwig's own spark, I'm not sure (I've never actually read the book)—it becomes a bittersweet rumination of the interplay of memory and the passage of time within a family unit and the ways in which adulthood transforms sibling relationships and inevitably scatters and isolates siblings from one another. This—along with some judicious tweaks of iconic scenes from Gerwig's screenplay, to say nothing of the cast's work in sculpting these characters—magically makes some of the story's more befuddling and flat choices (e.g. Amy and Laurie, Jo and Bhaer, etc.) feel like rich and melancholy realities of growing up. This is no more true than in its depiction of Beth's death, which, in most versions of Little Women I've seen, has always felt somewhat like a forced dramatic climax to a story that isn't really in need of a climax. But Gerwig's split structure gives Beth's fate a weight that goes far beyond the loss of a sibling; it is a manifestation of the unstoppable march of time and how it robs and pillages from childhood, how it fundamentally imbues memory and the self-identity built upon those memories with a twinge of pain. I found myself thinking a lot about my own brother, who died in October, and how the pain of his death was not just on the basis of his death in and of itself but also on the ways in which it bifurcated the lives of me and my siblings into a Before and an After and threw into relief the whole host of changes my family has undergone, both big and small, that have made life a little sadder, a little more complex, a little richer. There's a way that the wholesome purity of the Little Women story can feel a little precious and alien in relation to lived experiences, but the fundamental triumph of this particular version is that it's not just the story of this one family rendered in deep emotional hues but also so achingly real at every turn that it becomes, improbably, the story of families writ large. To turn to the old adage about how the specific becomes the universal in fiction would damn to the realm of cliché a movie that sails beyond the dichotomy of "original" and "cliché" into the realm of Truth. A complete triumph. As advertised, one of the best of the year. Grade: A

Uncut Gems (2019)

Basically a two-hour stress attack. For those of you for whom that sounds unpleasant, don't worry: it's also a very funny, very exciting thriller that's also a tremendous showcase for both a magnificent, throbbing score by Oneohtrix Point Never and a towering tragicomic performance from Adam Sandler. Sandler in particular is a marvel; as with his iconic Punch-Drunk Love performance, he knows how to take the particular quirks of his comedic persona and twist that into a terrifying intensity that feels both of a piece with his broader body of work and also complements the particular vision of the directors (here, the Safdie brothers, whose vision feels very much of a piece with the nightmare anxiety cinema of Good Time and Heaven Knows What). It also bears mentioning that I probably laughed more during this movie than I did during any of those Adam Sandler movies I had to watch this summer. Grade: A

Atlantics (Atlantique) (2019)

For a deconstructive ghost story, Atlantics is not nearly as oblique as it could be. It is, in fact, a pretty straightforward forbidden-love romance with a pretty straightforward class conflict as the backdrop: a woman is engaged to be married to one dude, but she is in love with another dude (that her family doesn't approve of); this dude is a construction worker whose boss is exploiting him and his colleagues. Even when the supernatural stuff starts creeping into the story about halfway through the movie, these threads still follow familiar paths. It's just that these paths weave together in unexpected and completely striking ways that feel as indebted to the folkloric slow cinema of Apichatpong Weerasethakul as they do to, like, Ghost and stuff like that. This isn't slow cinema, though, and the movie remains accessible and briskly paced throughout, animated by a row of truly great performances from its main cast and some stunning cinematography by Claire Mathon (who also shot Portrait of a Lady on Fire, which I haven't seen but by its reputation seems to be setting Mathon up for an all-time-great 2019). I was a little less thrilled about the conventional early stages of Atlantics, but once it gets going, it's spectacular. Grade: B+

The Art of Self-Defense (2019)

This movie adds absolutely nothing new to the cinema of deconstructed toxic masculinity that wasn't already done by the likes of Fight Club and stuff. But there are some extremely solid jokes in its extremely arch rendering of male social codes, and Jesse Eisenberg is pitch-perfect as the lead—his thousand-mile mannequin stare has never been better suited. Grade: B

Another Year (2010)

Mike Leigh has a knack not just for achingly humanist stories but for finding richly specific nooks of the human experience that often go unexplored. Another Year is, in many respects, a film about class and the anxiety and insecurity that comes out of the financial and social precariousness of the lower-middle class. But Another Year goes for none of the tried-and-true tropes of depicting class struggle, instead focusing on one single sliver of that experience: the ways in which the disorienting unsteadiness of being lower-middle class and isolated from others by the grinding machine of living in a capitalist system intersects your relationships with those who are just slightly more stable and comfortable than you are. It's a warm, tender, quietly wrenching story that finds its beating heart in its human characters, rendered brimming with life by the core cast of Jim Broadbent, Lesley Manville, and Ruth Sheen. Here at the decade's end, it seems like people have gone a bit quiet on Mike Leigh, and he's certainly not the flashiest director out there. But movies like this are a perfect example of just how much of a treasure his work is. Grade: A-

Television

The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Season 3 (2019)

This show's commitment to high-wire dialogue acrobatics and sweeping visual designs is still as on-target as ever, but Mrs. Maisel is running into some serious problems dramatically this season. It's increasingly clear that the series has no idea what to do with the privilege of its characters, which gets highlighted this season with Midge's arc on tour with a black (and closeted gay) musician, a plot with an intriguing premise but little payoff. It's also clear that the show has no idea how to grow these characters past the types established in the first two seasons; there's a lot of struggle on a scene-by-scene basis, but (with the exception of Susie, who this season gets probably the best arc of the show since Midge's back in Season 1) almost none of this coalesces into forward momentum or change, despite near-constant crises that would seem to warrant some kind of growth. The very final scene of the season seems to portend some pretty big changes on the horizon, and if Season 4 can use that to freshen up these characters, then great. But until that happens, we're left with a show comprised entirely out of scenes that are immensely enjoyable in the moment but have little dramatic tissue connecting it all together to move things forward. Grade: B

Books

The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien (1990)

I read this so I could teach it to my AP students this spring, but I'd been meaning to read it since forever anyway. I don't know why, but I'm surprised that it's as great as I'd heard. I was expecting an honest, emotionally intense short story cycle about the experiences of soldiers in Vietnam, which this totally is. But I was not expecting the metafictional elements at all, and they kind of blew me away, deflating a lot of the stodgy traditions of typical "vérité" war literature. So uhhh... if you're interested in taking AP Literature & Composition this spring, you'll get to hear me stan this book pretty hard. Grade: A

No comments:

Post a Comment