Hi everybody! So, last week I talked about doing a Q&A for my 400th post provided I got enough good questions. Well, I got enough question, so here's the Q&A! A lot more people answered than I expected, and some people whose names I don't recognize responded, which is exciting for me—I mostly didn't realize anyone but friends and family read this blog. Thank you for reading, internet strangers!

Anyway, I hope y'all enjoy this. I had fun answering these questions.

The Q&A:

My good buddy Andrew asks: "If you were mayor of Knoxville for a day, what would you do?"

For those of you who don't know me personally, I live in Knoxville, TN, so I guess this is my chance to flex my civic imagination, right? I'm assuming that this means I am not limited by things like procedure and due process, because the realistic answer to this question is that if I had only a single day as mayor, I could do basically nothing. But let's say I'm living in a fantasy where I can get stuff done in a day. So here I am, rising bright-eyed and bushy-tailed as the temporary mayor while otherwise Mayor Kincannon is on vacation or something. So I get to my office and start my ambitious agenda:

- I know Andrew wants me to say, "Put a sidewalk on the road his house is on," so I guess I'll start with that.

- I'm also going to end those inhumane police sweeps of homeless camps that the city seems so fond of lately. In fact, I'm going to reduce homelessness considerably by using eminent domain to seize the recently defunct Hotel Knoxville by the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame and convert it into emergency housing.

- Next, I'll establish a program through the Office of Neighborhoods that gives neighborhoods the ability to create community land trusts for the properties in their neighborhoods; that program also creates a function where properties that the city reclaims because they are abandoned or owe back taxes or whatever are automatically put into that neighborhood's community land trust.

- Finally, I would re-extend the city bus express line out to Turkey Creek and create a new line that goes out to Strawberry Plains (that way I can ride the bus to work). Then I would create bus lanes on Magnolia, Kingston Pike, Broadway, and Chapman Highway. People are going to hate this, since it reduces each of those to only one car lane in each direction, so it's a good thing that I'm only mayor for a day and Kincannon can deal with the fallout while I cruise around Knoxville in the now much faster city buses.

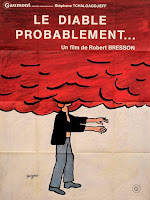

My friend Chris asks, "What Academy-Award winning film for Best Picture would you call the most undeserving of the title in the last 15 years?"

The 15-year range is a little unfortunate, because it makes it so that there's only really one possible answer to this: 2018's Green Book, which is not only undeserving compared to the other movies nominated that year (The Favourite? Roma? BlacKkKlansman?) but is also just a bad, nonsense movie on its own terms. If it were a 16-year range, then I'd have to make some hard decisions about whether or not 2005's Crash is worse (Brokeback Mountain should have totally won that year). My instinct is that it's probably Crash that's worst. If I ignore those two obvious choices, though, it becomes a lot more difficult for me to pinpoint the least-deserving. My general approach to the Oscars is that I'm content as long as a movie I like wins, regardless of whether or not it would have been the movie I would have picked, and the past 15-16 years have actually been pretty good for the Best Picture winners on those terms. Almost none of them would have been my own choice (Moonlight is the only one I probably would have chosen from among the nominees), but except for Crash and Green Book, I've liked all of them. That said, I remember almost nothing about The Artist (2011, when Tree of Life would have been my pick) or Argo (2012, a pretty weak year for Best Picture nominees, though I think Lincoln would be my favorite of the bunch), which maybe is a sign of how comparatively weak they are.

My pal Logan actually submitted three questions. His first is: "Are there any movies you hated at first, but afterwards loved, or vice versa?"

I don't rewatch movies a ton, so I don't have this experience as often as I might otherwise. But one that comes to mind is 2001: A Space Odyssey. I read the Arthur C. Clarke book in high school and loved it, so I immediately sought out the movie and was really turned off by how slow it was and by what I saw as the cheap psychedelia of the "Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite" sequence. I rewatched it probably 5-6 years later when I was going through the filmography of Stanley Kubrick, and that's when I fell in love. I think by that time I had seen a lot more movies with that sort of deliberate pacing, so I was better-equipped to engage with it on its own terms. As for the vice-versa situation: this is kind of silly, but I loved the direct-to-VHS Aladdin sequel The Return of Jafar when I was 4 or 5 years old, but as an adult, I've realized it's a trash movie through and through. Terrible animation, cardboard voice acting, dumb plotting—I can't think of a single good thing to say about it.

Logan's second question is: "What's the movie you've watched the most?"

At this point, it's probably one of the movies my son is obsessed with watching over and over, so that would be either Charlotte's Web (the 1973 movie with Debbie Reynolds as Charlotte), Bambi, or The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh. If I'm limiting this to just movies I've chosen to watch, though, it's probably The Emperor's New Groove. There was a time in middle school when I had the entire movie memorized—in fact, me and a friend were camping once and in the tent one night recited the whole thing from memory.

Logan's final question is: "What is the greatest comedy of the 2010s and why is it The Death of Stalin?

My rebuttal was almost In the Loop (same writer/director as Death of Stalin!) until I realized that it came out in 2009. So maybe The Death of Stalin is the best. Other contenders: Inherent Vice, Tangerine, The Nice Guys, Love & Friendship. I'm probably forgetting something else.

An anonymous reader asks, "What is your opinion on Red Velvet cake?"

I don't have a strong opinion. Like most cake, it is good. But it's not something I actively seek out when I get my dessert of choice.

Another anonymous reader (or maybe it's the same one from the last question) asks, "How have your tastes evolved since you first started this blog? Do your

current favorite albums and films still include your initial favorites?"

I've been doing this blog in one form or another since 2013, and if you go back and look at my yearly top 10s in music and film, that's probably the best indication of how my tastes have changed. If I had to summarize, I'd say that for film, I've become a lot more interested in experimental and foreign cinema and a lot less patient with franchise filmmaking (particularly as the MCU has become so dominant and intent on interconnectivity, which I find a little tedious). I've also become a lot more forgiving of movies that are not traditionally "good" but are nonetheless ambitious or messy in interesting ways. For music, I'm much less invested in indie rock than I was in 2013, though even at that time, I was already kind of falling out of love with that scene, and on the other hand, I've become much more invested in contemporary jazz and electronic music. So in conclusion, I guess I've just become an old, pretentious fart. Do my old favorite albums/films lists still include my current favorites? If I made those lists again, I would probably keep about 75% of each. Some of those, especially in the films, were works I had experienced pretty recently at the time but since have kind of faded from my memory—for example, I probably wouldn't put City of God on a list now because I haven't revisited it since I initially watched it and don't have as strong feelings for it as I did in 2016 when I made the first list.

Another anonymous question (I'm just going to assume these are all from the same person; we'll name this person "Julia"): "What’s something you’ve never been able to do well?"

Oh boy, where to start? I guess I'll stick with things that lots of people tend to be good at. I'm a terrible singer. Also, most things involving hand-eye coordination, including my ill-advised dalliance with baseball in middle school. I'm also generally pretty terrible at fast-paced first-person shooters like Call of Duty. Cursive writing is another thing that's always been pretty hard for me, to the point where I would get so stressed out about having to write it in 2nd or 3rd grade that I would start crying. In college, I wrote a research paper about why we shouldn't teach cursive in schools anymore, and I still stand by that claim.

Anonymous Julia asks, "What's something you're really good at?"

Honestly, really boring things. I'm great at washing dishes. I'm very good at Super Mario World (though not speed-runner good). I'm good at using public transit (a surprisingly uncommon skill in Tennessee). I also think I'm a pretty good writer, though I've as-yet had much success at publishing my work, so maybe that's just a delusion of grandeur.

Julia asks another question: "If you could steal any one item with no consequences, what would you steal?"

Are those time-turner things Hermione used to take extra classes in Harry Potter real? Because I have become one of those boring adults for whom Time is my most valuable resource, and I would love to have more of it. If I'm sticking with real objects, I would steal one of the industrial trains that runs through Knoxville and convert it into a passenger train, reintroducing passenger rail to my town after several decades absence.

Julia again: "What makes you feel old?"

Earlier this semester, I overheard a student listening to Nickelback's "How You Remind Me," and I was like, Wow, what a throwback. Then I realized that the song was 20 years old, and I was like, Huh, that's pretty old. Then I got curious what popular rock songs were 20 years old when "How You Remind Me" came out, and the first thing I found was Journey's "Don't Stop Believin'"—this whole train of thought made me feel incredibly old. Other than that, I do feel pretty old when I look at kids on TikTok, but generally I find that platform delightful, so I don't feel like a bad kind of old person. But then I hear kids talk about, like, 6ix9ine, and it triggers this involuntarily moralistic response in me—like, I cannot believe the kids these days are listening to such reprehensible, trash people. And that does make me feel pretty bad, because that's just an insufferable kind of old person to be.

Anonymous Julia strikes again: "If you could change the ending of any famous movie, which movie would it be and how would it end?"

If I spent a lot of time thinking about this, I could probably come up with a better example. But right now, what comes to mind is My Fair Lady. It's absolutely ridiculous that Eliza comes back to Henry Higgins at the end; he's an arrogant, insufferable prick, and they should not be together. The narrative builds really satisfyingly to Eliza leaving him for good, and if I were writing the ending, Higgins would sit alone, listening to the recording of Eliza's voice, and then the credits would roll. None of this her popping back in to give a happy ending business. I realize this isn't the movie's invention; it's in the stage musical, too. But it's heinous and sullies an otherwise delightful experience.

Adam says, "Thank for your blog - it is an interesting and informative take on film.

I do wonder, with a full-time job and family, how do you find time to

watch so many movies a week?"

Very obsessive time management, I guess. I'm pretty good at getting into daily rhythms, and part of those rhythms usually ends up finding a 90-ish-minute pocket of time for movie-watching. The other day my students asked me if I would rather have more time or

more money in my life, and I my answer is Time, in a landslide. I'm constantly running over in my head how I will have time for the things I want to do: not just watch movies, but write, read, spend time with my wife and son, play video games. I think everyone does this to an extent; I'm not going to pretend like there aren't people who are busier than I am, but also, a lot of the people I know just prioritize their time differently than I do. In the time that I would spend watching a movie, other people might be, say, on TikTok or binging a TV series or gardening or hanging out with friends (note: I do have friends, and I hang out with them [esp. in non-COVID times]—I'm not a total loser! But also, I'm much more introverted and content to stay at home than some people are). Another part of this is just the luck of my particular life circumstances right now—for example, I usually have about an hour to and hour and a half between when I get home from school and when my wife gets home from work, and because of where my son is currently at daycare, it makes more sense logistically for her to pick him up (I should also mention that it's key that my wife is accommodating of my hobbies)—last year, though, I was the one picking him up, so I had to find movie-watching time in the evening, after he went to bed. During the holidays, when I'm home with my son, I usually watch a movie during his afternoon nap. We have another kid on the way who will be born later this summer, though, so we'll see how well I can juggle all this when there are more than one little creature vying for my attention and care. Speaking of time management, I've spent a lot of time answering this question, so I guess I should move on.

Anonymous Julia pops back in again for another question: "This may be too personal and I understand if you don't desire to answer.

But from reading your reviews, I feel we may share a common struggle

with some tenets of Christianity. Would you still describe yourself as a

Christian and if so, how does this view reflect the lens with which you

view (and review) movies?"

If teenaged, Evangelical me were to time travel to the present day and ask me some theological questions, he would have some strong disagreement with my answers. I've come a long way from my Evangelical upbringing, and in a lot of ways, the mystical and socialist Christianity I practice now doesn't really resemble the conservative Christianity I grew up with. But I'm still a Christian, and I even attend a fairly orthodox church. It's just that now I have a much more open-handed approach to my faith than when I was younger. In particular, there are a few things that are central to my faith now that I either had no clue about a decade or two ago or would have outright rejected:

1) the importance of community and collective action (not necessarily the political kind, but not necessarily not the political kind either) in Christian life

2) the importance of people's material (not just spiritual) circumstances

3) the centrality of solidarity with the oppressed/marginalized within the gospel

So as far as how that affects my movie-watching lens, I guess first and foremost I deeply appreciate when films engage those ideas, both when it comes to movies that are trying to depict Christian faith in some way and also movies that don't seem particularly interested in faith. On Letterboxd, I made a list not too long ago about my favorite faith films of the 2010s, and if you look at that list, a significant chunk of those movies aren't explicitly faith-based; still, they were meaningful to me about faith on some level because of how they dialogued with facets of my beliefs. It's tough, though, because the vast majority of explicitly Christian movies are not in dialogue with my beliefs. Instead, they are either doing that kind of smug dunking on a strawmanned Christianity (I'm thinking of a movie like 2000's Chocolat, starring Juliette Binoche and Johnny Depp) or they are basically preaching this extremely thin Evangelical morality whose sole purpose is to joust at culture-war windmills or get someone to say the Sinner's Prayer (think the Evangelical film industry: Facing the Giants, God's Not Dead, etc.). Particularly with that latter kind of movie, I can't stand the way that those films cheapen the profound meaning I find in Christianity into this stupid trinket of cultural identity that's supposed to get you into Heaven, and to add insult to injury, they're usually just dreadfully made, too. So I guess another big part of how this affects me as a Christian movie viewer is the fuming anger I feel when I watch, like, Pure Flix movies and that kind of thing, an anger I think will surprise nobody who has read my reviews of the God's Not Dead movies, for example. Funnily enough, what I just said is probably one of the few things the time-traveling, teenaged me would agree with modern-day me about with faith. I've always hated Christian™ movies.

Jenee asks, "What's the worst movie you have ever seen?"

This is a hard question, because I don't actually watch that many bad movies, since I usually watch movies I already have a good idea I'm going to enjoy. I'm tempted just to say God's Not Dead. That movie makes me miserable. But it's also too weird and too unintentionally hilarious in its hatefulness to truly be the "worst." So I think I'll instead go with another contender for worst-faith-based film of the 2010s: Sausage Party, which I gave a higher grade on this blog than God's Not Dead, but for the life of me I can't remember why.

Surf Knoxville (I'm guessing that this is a pseudonym, but I'm hoping it's not) has the next question: "Thank you for your blog, I look forward to it every Monday. Your

reviews focus on box office films, with some foreign films thrown in and

very rarely, if any, documentaries. Why is this?"

This question caught me off guard, because I feel like I do watch and review a fair number of documentaries. I love a good documentary. But glancing back over the movies I've watched in the last couple months, I actually haven't seen that many docs. So I guess I've been going through a dry patch recently. It's not an intentional one. Maybe part of the issue is that I choose around 60% of the movies I review on here by going to the library and walking the movie shelves until I see a movie that looks interesting—since my library sorts the documentaries separately from the narrative films, I usually am not grabbing documentaries on these library trips.

Marian asks, "Do you feel that films function as an avenue for a producer to deliver his or her worldview to a captive audience?"

I think all art communicates ideas, whether or not the artist intends to or not. So yes, I do think that movies convey ideas or worldviews, though I would push back against the "captive audience" part, since it implies that we as viewers are just passive empty vessels for people to pour ideas/worldviews into. Viewing can be a participatory activity, too, where we actively engage with the ideas presented by a movie. Whose ideas is a tricky question to answer, though, because movie-making is so collaborative. If by "producer" you mean the people credited as "Executive Producer," etc., in the credits, I think it's pretty rare for those people to be the central voice of a movie, though in big franchises like the Marvel movies, there does seem to be a fair bit of producer input. The stereotypical movie "author" that film critics tend to identify is the director of a movie, and there are certainly movies that seem to come with a particular director's stamp—movies directed by David Lynch definitely all feel like they strongly reflect something of the personality/ideology of Lynch himself, and certainly it's not an accident that Ingmar Bergman, the son of a Lutheran minister, made so many films about Christian faith. Other times, the writer is more the author (if that writer isn't already also the director). But then you have a movie like The Wizard of Oz, which has a pretty particular worldview but also has such a large stable of writers and directors who were involved with its making (to say nothing of the army of actors, costumers, musicians, and other folks who also helped make that movie such a singular piece of art) that it's hard to say who exactly is responsible for the perspective the completed film has. And then you have experimental movies without narrative, whose ideas are much more abstract, sometimes even just explorations of sounds or images—what does an audience get out of something like Stan Brakhage's "Black Ice" except just the sensory feeling of those flashes of color? I guess what I'm saying is that it's complicated.

Anonymous Julia's back again with the tough question: "Can a movie be appreciated solely on its merit, or do the life choices

of the producer and any prominent actors/actresses need to be taken into

consideration (i.e. Woody Allen, Harvey Weinstein)?"

I have no good, comprehensive answer to this. But I do think that as a general principle, the behavior of artists should be taken into account, even if it doesn't stop you from actually watching the thing. Let's use Woody Allen specifically as an example. The way I see it, there are varying tiers of movies when it comes to a problematic creator like Woody Allen:

- First, there are Woody Allen movies that (besides Woody's involvement in the production) have basically nothing to do with the fact that the man almost certainly abused Dylan Farrow—for instance, Broadway Danny Rose is a great movie, and besides the presence of Woody Allen and Mia Farrow, it more or less has no connection with any of Allen's more troubling behaviors/tropes. So it's not like I can completely separate it from Woody Allen and what I know about him—it's definitely in my mind. But I don't usually have much angst about watching movies like that. Those who do get bothered by them will say that seeing any movie by a terrible person contributes economically or culturally to that terrible person's power, which is a position I'm definitely sympathetic to, but I also get so overwhelmed thinking about how to make sure my cultural engagement doesn't enrich the powerful and oppressive that I basically can't engage with that. I guess that's a lazy response, ethically, but there you go.

- Then there are Woody Allen movies that have a thematic or meta connection to his behavior—take, for example, how so many of his movies involve an older man in a relationship with a woman much younger than he is (Mighty Aphrodite, Magic in the Moonlight, etc.) and especially the one in which Allen himself plays a character in a predatory relationship with a minor (Manhattan). I struggle with these, and something like Husbands and Wives (made around the time of the dissolution of his relationship with Mia Farrow [some of which hinged on the allegations surrounding what he did with Dylan] and intended to closely mirror it) becomes excruciating when viewed with the real-world context in which it was made in mind. If it's ever possible to "separate the art from the artist," these are definitely cases where that's basically impossible. That said, I do think it's possible to get some pretty profound meaning out of the tensions such movies create, so I guess my wishy-washy answer is that my posture toward a movie like this involves evaluating just how fruitfully the film can be viewed through that lens. This is outside of the Woody Allen sphere, but Rosemary's Baby is probably the definitive example of this category in my mind: a deeply anti-rape, even feminist movie directed by a man (Roman Polanski) who within the decade would himself rape a girl (I'm not being colloquial; she was only 13). This biographical information makes the movie much more upsetting, but I think it's also constructive to think about how someone who could make a movie like Rosemary's Baby could also go on to rape someone (a minor, no less). There are a lot of people who simply cannot or do not want to dwell in this tension with a movie, and I certainly understand that position, because I can't always do that myself. I'm pretty inconsistent about this one, so it's not like I have some well-thought-out ethos guiding my approach.

- Then there are movies in which the making of the film itself is the product of misdeeds or otherwise tied up in the misdeeds of its creator somehow. As far as I know, there aren't any Woody Allen movies that fit this category, so I'm going to have to go outside his filmography for an example. Let's take The Shining; it bothers me deeply that Shelley Duvall was more or less abused on set in order to get the onscreen reactions Kubrick wanted from her (this is also true of the production of The Exorcist—horror movies have a pretty bad track record re: treatment of its cast/crew). In fact, it bothers me to the extent that, while I respect the movie overall, I really don't particularly like the movie anymore or even want to think about it much now that I've come to understand what went into making it. I mean, there are movies (famous movies) where people have died because of unsafe filming conditions, and that shakes me. But again, I'm not very consistent about this, and I can't claim to have strong scruples about it. The production of The Wizard of Oz involved some pretty bad mistreatment of the little people who played the munchkins, but I love that movie, and learning about that hasn't changed how I feel about the movie. If I were a completely moral person, I probably wouldn't have anything to do with these movies, and I do feel like that about some movies—but not all of them, and I can't give you a good reason why.

Coming back around to the original question, I guess my point is that in all of these cases, I don't think it's possible to appreciate a movie "solely on its merit," because what the merit of a movie is in the first place is relative to its context. A. O. Scott has a pretty insightful essay on Woody Allen that I think about a lot in this regard, and the ideas there seem relevant to a lot of creators, I think. Basically, I think the question is formed on a false dichotomy between "merit" and biography—the two are often inextricable. I just don't have consistent rules about whether or not this means I engage with or experience a movie like that. I respect people who have more a rigorous stance on this issue, though, because I think they probably have a more coherent ethical framework on the issue than I do (though I'd bet everyone has their arbitrary lines they draw for stuff they really love). Anyway, I have typed a lot of words in answer to this, so I hope this ramble makes sense.

Hot on the heels of that epic question comes Anonymous Julia again: "What is the most thought-provoking movie you have ever seen? One where

after viewing, you just had to sit there and contemplate for hours?"

This probably won't surprise anyone who knows the preoccupations that rule my spiritual life, but the two movies that immediately came to mind when I saw this question were 2017's First Reformed and 2014's Noah. They're both movies about what it means to be a person of faith in a world that is deeply broken by seemingly immovable powers of oppression (powers that we might also be complicit in), and the questions these movies pose are still rolling around in my mind. Both of them (especially First Reformed) are also pretty heavily informed by the work of Andrei Tarkovsky and Ingmar Bergman, so I would be remiss if I didn't also give a shout-out to Winter Light, Through a Glass Darkly, and Nostalghia, movies that have also left me breathless and challenged and which I still think about a lot. But I'm an English-speaking philistine, so of course it's the English-language movies I think about more.

Another one from Anonymous Julia: "I am a fan of older movies where a single camera followed the action.

Sure, the action may not be as fast-paced as today's films, but that is

part of the appeal for me. With today's rapid cut scenes and shaking

cameras, I feel as though I'm having a seizure. Do you prefer the

slower-paced, more conversation and relationship-driven movies, or ones

with the fast action and rapid cut scenes?"

I'm a little confused by parts of this question. Older movies still used multiple cameras and plenty of editing; the Psycho shower scene has something like 50 cuts in under two minutes, and that movie's 60 years old. Older movies weren't necessarily relationship-driven either—look at a Marx Bros. movie or a lot of Chaplin's films. I think there are also plenty of modern movies that are slower-paced and/or are relationship-driven, and audiences are still watching them (for example, Greta Gerwig's adaptation of Little Women was one of the most popular movies of 2019). But I do think that the major studios (especially Disney) are increasingly disinterested in doing big promotional pushes of movies that aren't action blockbusters, and action filmmaking is certainly more chaotic and fast-paced on average than it used to be, so I guess I understand the spirit of the question. I'm afraid that I don't have a particularly interesting answer, though. I don't really have a preference between the two types of movies mentioned in the question: there are conversation-/relationship-driven movies I love, but there are plenty I find insufferable, and the same goes for modern action movies. I thought Red, White and Blue was excellent but found Wild Mountain Thyme to be dreadful; I'm pretty tired of the Marvel movies, but I've really enjoyed the last few Mission: Impossible movies. That's not to say that I don't have tastes and preferences; they just don't tend to fall along a relationship-driven/action-driven dichotomy. That said, I do get really tired of pointless handheld/shaky camera, though I would also point out that this isn't limited to just action movies—slow-paced European dramas are terrible about relying on some misguided idea of "realism" as signified by handheld camera. But I like a lot of those, too, so I dunno.

Okay, and now the final question. This one comes from Louis: "Not really a specific question, but I'd love to hear your thoughts on

Robert Cormier since two of his books are in your top 100. Chocolate War

was incredibly formative for me in middle school. I think some of his

books are too dark and mean-spirited (Beyond the Chocolate War and The

Rag and Bone Shop), but others are deeply humane (I Am the Cheese,

Heroes) and I love how he doesn't condescend to young adults at all. He

also seemed like a sweet, mild-mannered Catholic man, which sort of

calls to mind the disparity between David Lynch's personality and his

work."

Oh yeah, you're speaking my language. It sounds like you and I have pretty similar experiences with Robert Cormier. I first ran across him when I was in 9th grade (I Am the Cheese was on an ALA list that I ran across), and it's probably not an exaggeration to say that that was the single biggest turning point in my reading habits I've ever experienced. I was immediately captivated and read almost all of his books over an 18-month span. I had never read anything like them: these dark, brutal, often unapologetically bleak novels with big ideas and, as you say, a steadfast unwillingness to condescend to young adults or even moralize plots. His work completely changed the way I viewed literature, and it definitely set the stage for how I would react to the stuff I would read in my Honors and AP English classes in high school, which expanded my view of literature even further. I definitely agree that his books could be pretty mean-spirited (Beyond the Chocolate War in particular feels borderline sadistic in the way it wrings characters through some extremely miserable, triggering situations), and back in 9th/10th grade, I struggled with this a good deal, since at the time these were far and away the most explicit books I had ever read involving sex and violence—I remember quitting Fade multiple times because of the content (there's an incest subplot that's pretty awful, if I remember right) before ultimately finishing it because I found the book so magnetic anyway. In the short term, this helped cultivate a (thankfully temporary) unhealthy streak in me where I thought that good literature had to be grim/depressing/edgy. But long-term, I have pretty positive feelings about Cormier, and even today, when YA is exploding in terms of the types of stories it tells, his work still feels revolutionary on some level. So much modern YA is explainy and has these heart-on-the-sleeve postures toward social issues, and while I see a lot of value in that, I do sometimes wish we had more authors who would have the kind of hands-off trust in YA readers to wrestle with thorny ideas that Cormier often showed. That part of his work still feels very vital and unique to me in the world of YA. That said, I haven't returned to many of his books as an adult, and I do wonder how much a lot of them would hold up for me. I did try once to teach The Chocolate War, which I still maintain is a great book, to my students as a text in conversation with the ideas about individualism and civil

disobedience presented by the Transcendentalists (this was an

11th-grader class), and a few female students expressed some discomfort with the overwhelmingly heterosexual and male POV of the book (e.g. the multiple instances of the book describing not just the boys ogling girls but also the body parts of the girls that were being ogled). It's not that there's not a place for that, especially in a novel that is so much about the abuses of the hetero-male posture, but my students pointing that out did make me realize that even though Cormier does occasionally have female characters/protagonists, he's still coming at most of his stories from a male-coded perspective that's limited in some ways.

And that's it! The end of the Q&A! Thank you, everybody, for your questions. I had fun writing these answers, and I hope y'all have fun reading them. Maybe I'll do this again sometime.